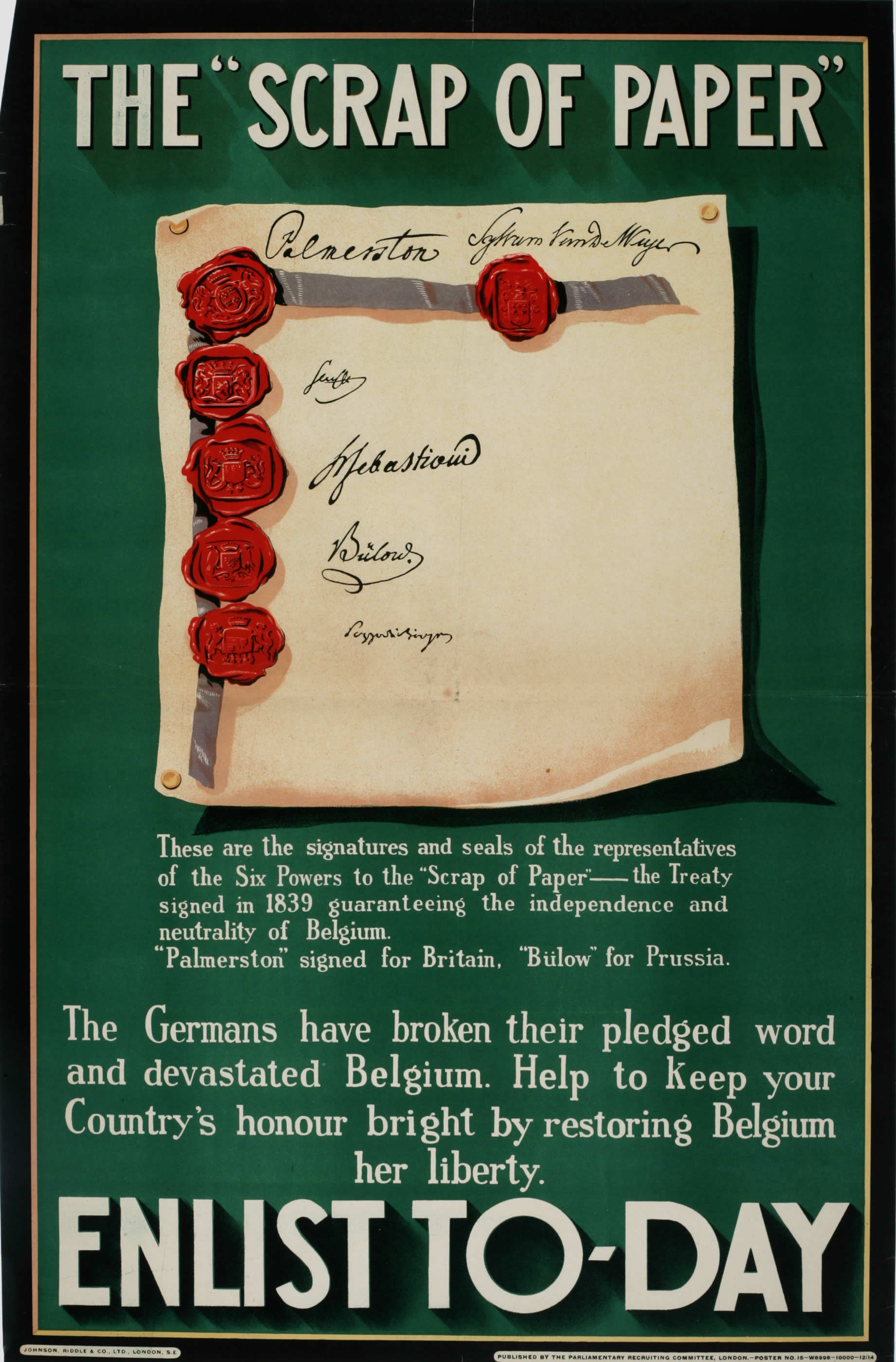

WWI BEGINS AND BELGIUM FALLS WWI was a confusing war, the kind that doesn't lend itself to facile movie tropes of good guys and bad guys. Belgium's experience during the war was tragic and complicated. To start with, Belgium had once upon a time been owned by the Netherlands, but in 1830, after much agitation, they finally got their independence. This was made official in the 1839 Treaty of London, which required Belgium to remain perpetually neutral and the other European powers who signed the treaty (Austria, France, the German Confederation lead by Prussia, the Netherlands, Russia, and the UK) to respect that neutrality. The century turned, and various other international alliances and relationships around Europe were set in place like a row of dominoes. Then, on June 28th, 1914, the assassination of Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand toppled the dominoes, and within weeks the big players in Europe were fighting each other.

HELPING DISPLACED TOURISTS In 1914, Herbert Hoover was an American financier with a background as a mining engineer. He was living in London in August, when the war broke out. Tens of thousands of Americans abroad found themselves stranded when their papers and money were no longer good and normal ocean traffic was interrupted. Hoover, already a wealthy man with many connections, took on the complex work of helping them get loans, passage on ships, et cetera so they could get home. Such skill, diplomacy, and talent for administration did he show, that the American ambassador in London and several other key people soon came to him with a larger problem: starving Belgians. A RECIPE FOR STARVATION You may remember this lesson from third grade physics: the more moving parts a machine has, the more complex it is. A lever is a simple machine; a clock is a complex one. Systems work along the same lines. Complex systems make our society possible, but are vulnerable to breaking because there are so many more things that can go wrong. Ideally, a complex machine or system should be designed with redundancies and back-up plans and replacement parts, like the human body; however, man-made systems which evolve over time as a response to need are rarely planned this way. The global food supply chain today, and America's food supply chain, since we import from around the world as well as producing food for ourselves, is very complex and very fragile. In 1914, occupied Belgium was in deep trouble because of their disrupted food supply chain: as a small and highly urban country, Belgium didn't have enough farmland to feed all their people, so they imported most of what they needed to live. Vernon Kellogg, who worked closely in Belgian relief projects at the time, wrote in his book Fighting Starvation in Belgium that the country normally depended on importation for "50 per cent. of its food supplies (78 per cent. of its cereals)." But now the German army was eating what Belgium did produce, and Great Britain was blockading the country's coastline to prevent food and other supplies from getting into Belgium, since they figured any food that got through would only be taken by the Germans anyway and they didn't want to feed their own enemy. So Britain's gallant leap to defend Belgium's neutrality was almost as bad for Belgian survival as the German invasion was! As a Liberian friend once told me: the grass is always flattened when elephants fight. Belgium was the grass in this fight, and got trampled. Within Belgium, in the immediate emergency of German occupation, all industry ground to a halt, their usual exports were confiscated by the conquerors, factory workers were conscripted for service in German factories, many civilians were shot in reprisals for real or imagined acts of resistance, and countless people wandered dazed and without occupation or bread. Anyone could see that food was the first and primary need, and many energetic and public-minded men leapt to work on that problem. The principle players (in no particular order) were:

BATTALIONS OF ACRONYMS In Holland in late September, Shaler found that the Dutch, though willing to help, lacked the food surplus to supply Belgium, so he moved on to England and bought food there. Getting it back to Belgium was just as complicated as buying it: the British Navy blocked his efforts at sea, but the British government, at length, agreed to allow the food to be shipped to Holland, and the Dutch agreed to facilitate its transport over their border into Belgium. Shaler, meanwhile, sought the help of other Americans in London, and got connected to the American Ambassador, Walter Hines Page, who knew of Herbert Hoover's organizational feats in getting American tourists and ex-pats home. All the resources previously dedicated to helping stranded Americans now shifted to the pressing problem of Belgium. Meanwhile, Belgian delegates, including Francqui, arrived in London to appeal for help. All of this involved telegrams back and forth with Washington DC, negotiations with the British and German governments, and delays. Finally, on October 22nd, 1914, one hundred and four years ago today, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) was set up as a neutral organization, with Herbert Hoover at its head. And in Belgium, Émile Francqui would head up the Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation (CNSA). HOW IT WORKED The first shipment of outside food arrived in Belgium on November 4th. But how did it get into the country, and how was it distributed? The answer is sufficiently complex that whole books have been written about it, but I'll simplify for the sake of this blog. Money came from private donors, the personal accounts of the wealthy men in the organizations, the Belgians themselves, and loans to the Belgian government by the British and the French. Food was purchased around the world, often from neutral countries and through neutral ports, but also from Great Britain, with a bunch of stipulations on how it would be transported and used. Obviously, the hostile parties fighting over Belgium would not agree with each other to help the country: Germany considered the starvation problem to have been caused by the British with their blockade, and the British military held that it was Germany's responsibility to feed the Belgians whom it had conquered. They wouldn't talk to each other, but, with great delicacy, bluff, and occasional bullying, Hoover got each side to talk to and make agreements with him, the neutral head of an aid organization. Food was packaged into specially labeled sacks that were stamped with the CRB information and were legally considered the property of the neutral Americans. It was shipped into Belgium from Holland with permission from the Germans, transported under a triangular white flag with red lettering "C.R.B". At this point, micro-management was actually necessary: the Belgians couldn't take charge of the food and distribute it themselves, because they were subject to German authority, and therefore could be ordered to turn the food over to the Germans. The only way to get the food onto Belgian plates was to keep it under American control up until the last possible minute. The CNSA organized thousands of Belgian and French workers to transport and distribute the food, but always under the supervision of CRB "monitors". The numbers here are interesting: 40,000 Belgians, 10,000 French, and 40 Americans at any given time. So once in Belgium, the work was done by locals, but the Americans were responsible to various international parties (the Allied powers, the international donors) that the aid was only going to Belgian civilians, not the German army. When the Americans entered the war on April 6th, 1917, it didn't stop the CRB's work, only shifted its agents a bit. Outside the country, the operations continued as before, headed by Herbert Hoover. But once the food entered Belgium, it was under Hispano-Dutch control: the food was now considered Spanish or Dutch, and the monitors overseeing the distribution were from those still-neutral countries. I spoke earlier about man-made systems becoming increasingly complex as they respond to the needs of the day: so the CRB became, over time, more like a nation than an organization. The Dutch and the Spanish both suffered their ministers to be honorary chairmen of the board; the CRB had a fleet of ships like a navy, and negotiated on terms of equality with various governments. Truly astonishing! And at the head of this many-tendrilled creature was Herbert Hoover, using his talent for systems and organization to coordinate the whole effort. This micromanagement continued after the food was delivered: the CRB repossessed the flour sacks to prevent them from falling into the hands of the unscrupulous, who might have re-filled them with plaster dust and sold them on the black market as real flour. This would have defrauded the buyers and discredited the CRB. FLOUR SACK ART

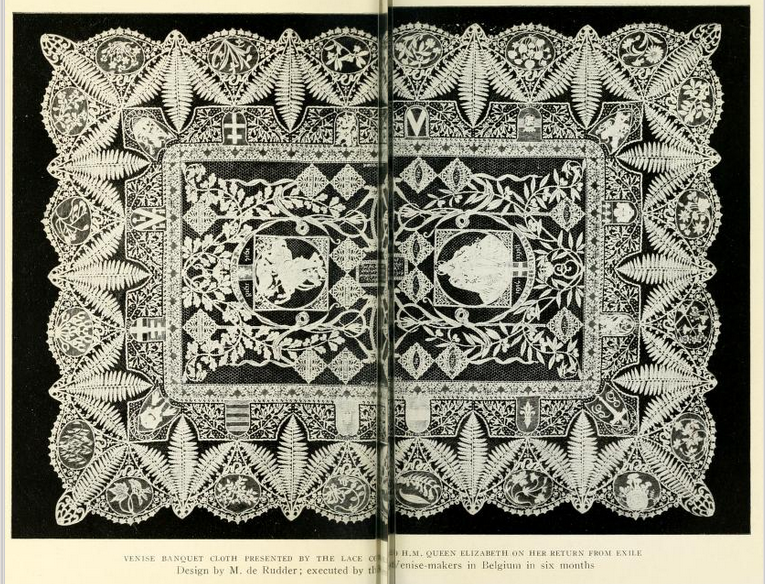

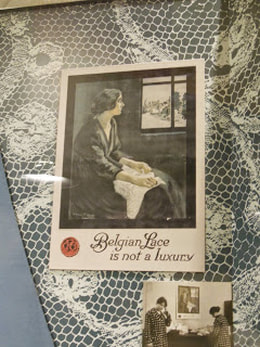

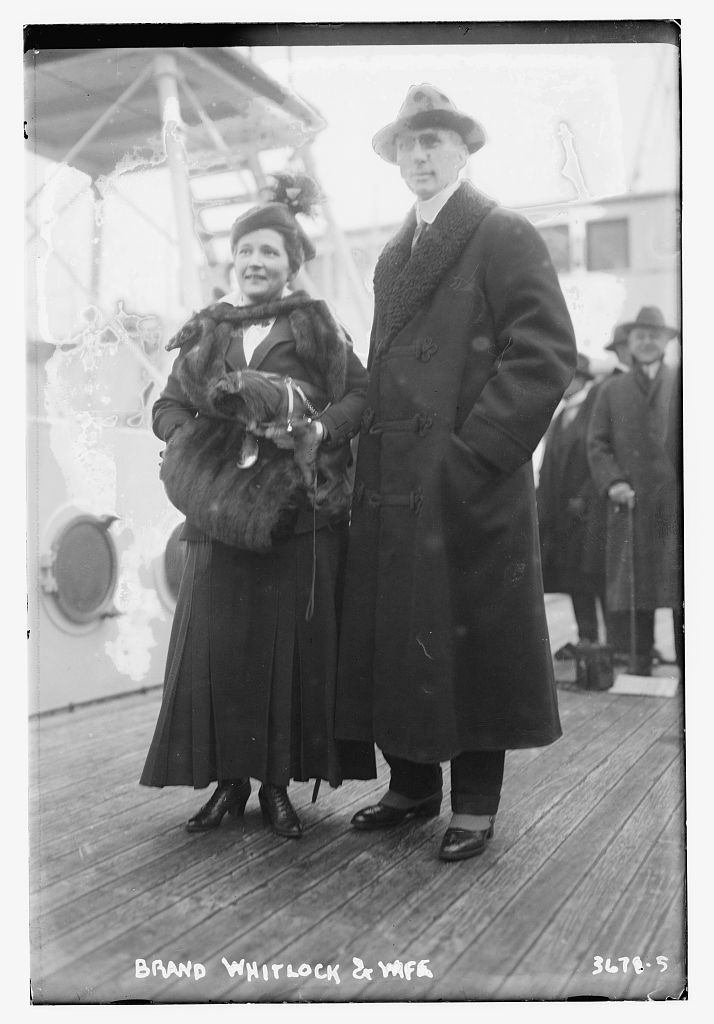

The flour sacks embroidered by Belgians in gratitude are a colorful example of this exchange of kindness, food, and industry. Check out some more at EmbroiderElaine's blog. BELGIAN LACE With the invasion, the Belgians recognized that their culture was under as much threat as their lives. Times were brutal and demoralizing, and they needed to bolster their identity. Now, Belgium had a long tradition of both bobbin lace and needlelace. At the start of the war, the industry employed an estimated 50,000 women, though that number accounts for just professional lacemakers, not including the average Belgian woman who often had bobbins and pillow in her house for personal use. Lacemaking schools were generally run through convents, and each city had its own favored styles. Though skilled laborers, lacemakers had always suffered from underpayment and poor working conditions, and so were a favorite charity of wealthy women. In 1911, prior to the war, Queen Elisabeth had encouraged the creation of the Amies de la Dentelle (Friends of Lace), composed of well-to-do patrons of the art who insisted on clean and safe working conditions, reasonable hours and pay, and proper instruction in the schools they bought their lace from. Then came the invasion, and by November 1914, the Amies de la Dentelle had formed a new committee: the Brussels Lace Committee, and put at its head Ella "Nell" Whitlock, wife of the American Ambassador. Under CRB aegis, a limited range of Belgian products went out, with the strict stipulation that they would be sold abroad only for relief efforts. "Another particular concern to Hoover was the plight of Belgium's renowned lace workers. Deprived of essential raw material by the invasion and subsequent blockade, a workforce of forty thousand women faced destitution, long-term idleness, and possible attenuation of their skills until Hoover and his associates stepped in. The CRB arranged to import needed thread for the lacemakers and to sell some of their finished products abroad. It also helped committees make advances to the women for their unsold production, such money to be recovered from the export of accumulated merchandise after the war. In these ways an entire industry was kept alive and thousands of skilled women self-supporting. The sale of the exquisite lace in England and the United States also no doubt helped to sharpen "the club of public opinion" that Hoover wielded in behalf of Belgium's cause."  ". . . a banquet cloth to be offered to Queen Elizabeth on her return from exile . . . Two hundred and twenty details, there were, on which during the darkest days of the war, women had worked with unfaltering faith and love. M. de Rudder, a well-known Belgian artist, had drawn the design for the Lace Committee. The border, edged with ivy, the symbol of endurance, is composed of ferns and wild flowers, eels and sea-weed, suggesting the forests and fields and waters of Belgium." From the book Bobbins of Belgium, by Charlotte Kellogg. Click the picture to see the digitized book, which is well worth a read! Lacemakers before the war had found patronesses and protectors in the wealthy women of Belgium; during the war they found benefactresses and allies in the wives of the CRB men and the wealthy women of the world who were eager to help Belgium. Ella Whitlock worked with her husband to secure concessions and agreements by which thread could come into the country. For each pound of thread imported, a pound of lace had to be exported (to ensure that the thread wasn't being used by the conquerors, I guess). Then Hoover's wife Lou took a role in selling the lace in London, Paris, and New York to raise money for more aid. Charlotte Kellogg (wife of CRB director Vernon Lyman Kellogg), traveled much in the country before America's entrance into the war and wrote a wonderful book about the Belgian lace industry, with a particular focus on bobbin lace. It's called Bobbins of Belgium and has been a source for some of the information in this post! Earlier in this post I praised Herbert Hoover for his work. Now I take a moment to do the same for these ladies just named. The social conventions of the time were to refer to them as "so-and-so's wife" or "Mrs. MALE NAME", as though they were appendages, but I wish to credit them as themselves: women of heart and courage and diligence, who gave of themselves to help others. Their husbands were blessed to have them, and so was Belgium! The Belgian lacemakers responded with enthusiasm and artistry. As with the flour sacks, they customized their lace with notes of gratitude and tributes to their helpers, like this one, a whole tablecloth of mixed bobbin lace and needlelace, with the American and Belgian shields as well as the Whitlock family crest worked in needlelace. Or this tablecloth embroidered with "To Mrs. Brand Whitlock grateful tribute from the Belgian lace makers". Since I can't find un-copyrighted images which I can use here, I'll provide links instead. Three examples of the American eagle and other US symbols in bobbin lace The Delicate "War Laces" of World War I Women in World War I - Belgian War Lace (Scroll to the bottom and click through the collection! So lovely!) Whitework, eyelet lace (broderie Anglais), and needlelace insertions AFTER THE WAR Various people from this history got various awards, titles, and recognition for their work, but that list would be less interesting than a brief history of what they did with themselves after the war. HERBERT HOOVER went on to become the President of the United States (1929-1933). Ironically, he became unpopular in the US when the Great Depression struck during his administration. Hoover, a staunch believer in charity as a private initiative and the value of civic action and volunteerism, gave personal aid to many people but opposed Federal aid until late in his term. Since he was modest about his own good deeds, and nervous to speak publicly, his opponents painted him as cold and indifferent, and he was defeated handily in the next election by the gregarious Franklin Roosevelt and his government-interventionist New Deal. So Herbert Hoover, a man who'd worked tirelessly to feed millions, was ousted from office as an uncaring elitist! Hoover continued in public life as a force of Conservative opinion, opposing the US entry into WWII. After WWII, in March 1947, he penned an economic report about the state of Occupied Germany which shaped Allied policy toward its re-building and the revival of Europe. He also organized food for German schoolchildren in American and British Occupied zones of Germany, supplying what came to be called "Hooverspeisung" (Hoover meals). After that, he organized things in the Executive branch of the Federal government for two different presidents. In his retirement, he wrote books and was active in charities. He died in 1964 after a very useful life. LOU HOOVER was notable for being a regular speaker on the radio, advocating the Girls Scouts and volunteerism, and supervising the design and building of the Presidential retreat Rapidan Camp. She died of a heart attack in 1944, twenty years before her husband. ÉMILE FRANCQUI turned his post-war energies to education, founding the University Foundation to encourage Scientific research in Belgian Universities, and being involved in various related institutions. In 1931, at the request of his King, Leopold III, he also set up the Institute of Tropical Medicine to work for the promotion of health in the Belgian Congo. Collaborating with Herbert Hoover again in 1934, he set up the Fracqui Foundation to support basic research in Belgium. BRAND WHITLOCK continued serving as Minister to Belgium, and was upgraded to Ambassador in 1919 when the US upgraded its Ministry to an Embassy. He served until 1921. He also wrote various novels and non-fiction books. He died in 1934. His wife, ELLA BRAINERD WHITLOCK, died in 1942, in France. CHARLOTTE KELLOGG did wonderful work with her pen. In 1920 she published a biography of Désiré-Joseph Mercier entitled Mercier, the Fighting Cardinal of Belgium. She befriended and assisted Marie Curie, outlived her husband Vernon, and kept writing. She died in 1960. VERNON LYMAN KELLOGG was an entomologist by training, and his pre-war work was mostly about bugs. But WWI had introduced him to humanitarian work and kindled in him a loathing of the ideas of social Darwinism which he saw as complicit in German militarism. His post-war work tackled humanitarian issues, food distribution, evolution, insects, and war memoirs. He died in 1937, so was spared the grief of seeing even more horrifying examples of the consequences of social Darwinist philosophy in WWII. WORKS CITED "Beadwork & Embroidery - CRB Flour Sacks." The UK Trench Art Site. Accessed 2/22/2018: http://www.trenchart.co.uk/Types/types18.html "Belgian War Lace." National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institute, 13 April 2017. Web. Accessed 2/22/2018: https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/281-artist-soldiers-belgian-war-lace-0 "German occupation of Belgium during World War I." Wikipedia. Accessed 2/21/2018: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_occupation_of_Belgium_during_World_War_I Goodsell, Suzy. "Flour sacks provide war relief." Taste of General Mills blog. 22 Jul 2011. Accessed 2/21/2018: https://blog.generalmills.com/2011/07/flour-sacks-provide-war-relief/ History.com Staff. "America enters World War I." History.com: This Day in History. A+E Networks, 2010. Accessed 2/22/2018: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/america-enters-world-war-i Jorie. "Remember Belgium." EmbroiderElaine, 26 May 2015. Accessed 3/2/2018: http://embroiderelaine. blogspot.com/2015/05/remember-belgium.html Kellogg, Charlotte. Bobbins of Belgium: a book of Belgian Lace, Lace-Workers, Lace-Schools and Lace- Villages. Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1920, New York and London. Accessed 2/23/2018: https://archive.org/details/bobbinsbelgium00kell Kellogg, Vernon. Fighting Starvation in Belgium. Doubleday, Page & Company, 1918, New York. Accessed 2/22/2018: https://archive.org/details/fightingstarvati00kellrich Nash, George H. “An American Epic: Herbert Hoover and Belgian Relief in World War I." Prologue Magazine Spring 1989, Vol. 21, No. 1. Web. Accessed 2/21/2018: https://www.archives.gov/publications/ prologue/1989/spring/hoover-belgium.html Thompson, Karen. "The delicate 'war laces' of World War I." O Say Can You See? Stories from the National Museum of American History , 19 August 2015. Accessed 2/21/2018: http://americanhistory. si.edu/blog/delicate-war-laces-world-war-i Unknown Belgian Lacemaker(s). American, Belgian and Whitlock Family Symbols Tablecloth, 1914-1918, The National Museum of American History (Smithsonian Institute), http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections /search/object/nmah_626122. Accessed 2/22/2018 Unknown Belgian Lacemaker(s). Majestic Needlepoint Cloth w/ Heraldic Coat of Arms, 1914-1918. Private collection, photographed by Maria Niforos. Accessed 2/22/2018: http://www.marianiforos.com /linen300detail.html Women in World War I -- Belgian War Lace. The National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institute Online Collection. Accessed 2/21/2018: http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups /women-in-wwi/belgian-war-lace FURTHER READING Miller, Jeffrey B. Behind the Lines and WWI Crusaders. See the website for info about the books: http://wwibehindthelines.com/ Online exhibit of war laces: http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/world-war-one-laces

A blogger views some lace in a museum in Washingon D.C.: http://christa-feelingblessed.blogspot.com/2012/08/a-lace-day-in-dc.html A short video/article about Hoover and his WWI work. (Pause video when it's done or it'll auto-play the next one. Scroll down to read the article.) http://www.ozy.com/flashback/how-herbert-hoover-saved-belgium/35372 Letters of Belgian Schoolchildren to Brand Whitlock: http://utdr.utoledo.edu/whitlock-imgs/

1 Comment

The Sister

11/1/2018 03:46:36 pm

This was fascinating material! Thanks for all your research! I liked this post a lot

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed