Today I contemplate Brutalist architecture, the Brutalist design philosophy, and how it might be expressed in thread. The photos in this post are all my own, of Mt. Hood Community College in Gresham, Oregon, USA.

0 Comments

Maybe quilting is a hobby people tend to take up in their middle years, as they settle into homes that have room for all the stuff, and as they age out of caring about fashion and clothes-sewing. Plus, a lot of young people exhibit their quilts on blogs and message boards (looking at you, r/quilting!) and Facebook, rather than in shows.

I wonder by what rubric we could actually evaluate whether an art is "dying"?

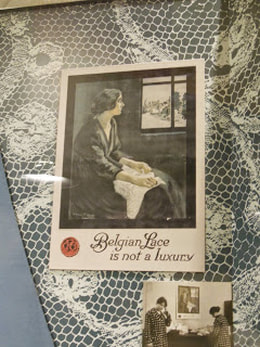

As for pictures, if I'm not using my own work, I seek photos under free public licenses. In today's post, however, I use one photo without permission (because I have no idea how to get permission). But then I mangle it beyond recognition in the pursuit of design, so I'm not sure where copyright law falls on that one! Nevertheless, I still do my best to credit the originator and link back.

Labeling quilts is an interesting topic for me. Historically, labeling quilts was not the norm. Some modern interpreters assume that the women of the past didn't think their work deserved credit, as this quote from Womenfolk.com exemplifies: Most women of the past simply didn't think that the everyday or even "for best" quilt they made was important enough to sign. Some even felt it would be too prideful to sign their quilt. I hesitate, however, to argue motives from a lack of evidence. We have positive evidence of makers marking their quilts in several instances, such as when making signature quilts as gifts or community projects, or when labeling a quilt for laundry purposes. Even the source cited above, which claims women failed to label quilts because they thought their work unimportant, then goes on to describe an uptick in labeling when indelible inks came on the market. Did women suddenly find their quilts important then?

Unsigned quilts were exhibited at county fairs, shipped across the ocean as gifts, saved for generations, and described in letters. Clearly they were not unimportant, even if they went unsigned. So maybe there are other explanations for not signing. Maybe the makers lived in smaller communities than we do today, and within those communities the people who mattered knew who made what. Perhaps the makers didn't care about a hundred years down the line because they never expected their quilts to last that long!

This will be a long post, mostly concerning the fire in 1911 and the pro-labor legislation that followed in America, but also touching on the global sweatshop problem today. Make some tea and join me for a talk.

In September of 1666, the Great Fire of London burned for five days, reaching temperatures hot enough to melt pottery and completely cremate victims, destroying thousands of buildings, and leaving seven eighths of Londoners homeless. In addition to devastating the city, the disaster ignited religious and ethnic hatreds, stirring mobs to violence and politicians to a blame game, and threatening the newly restored monarchy. London had been a medieval town, outgrowing its own streets and buildings, but after the fire it was rebuilt, with much the same street plan, but wider streets, better sewage disposal, and fire lanes to the Thames.

In 2014, PBS released a four-part miniseries dramatizing the Great Fire, which is compelling as history, drama, and costume-feast-for-the-eyes. And I... I love those things!

|

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed