|

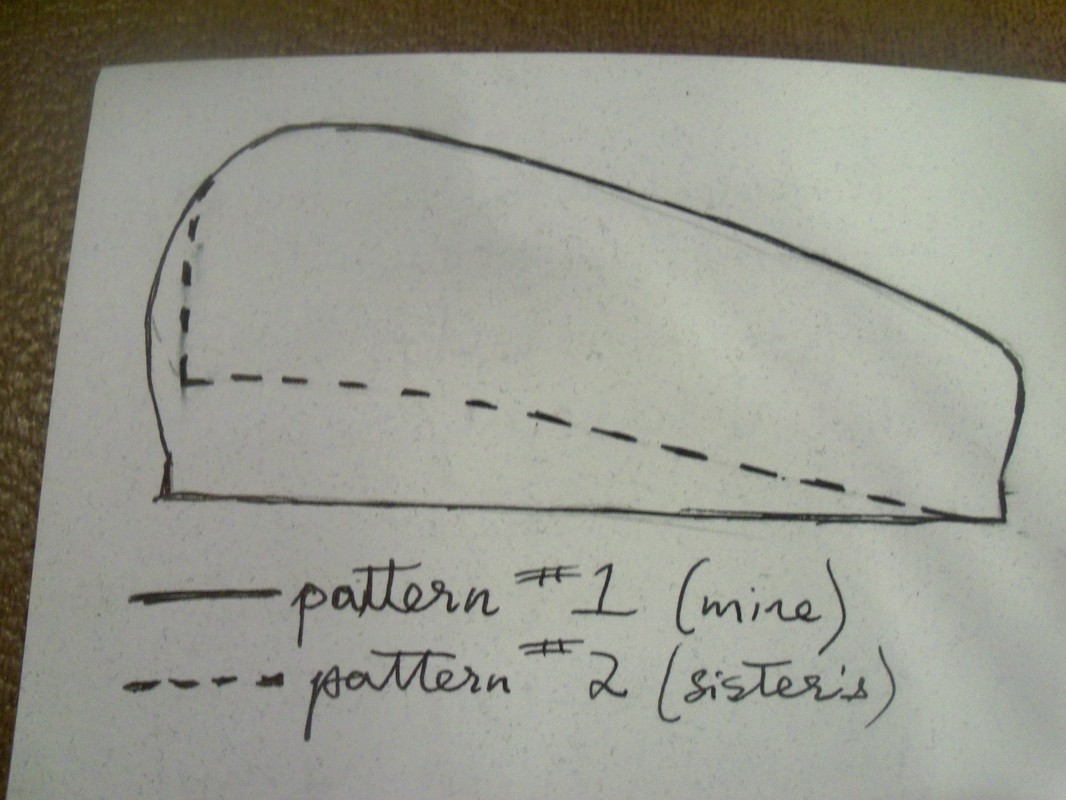

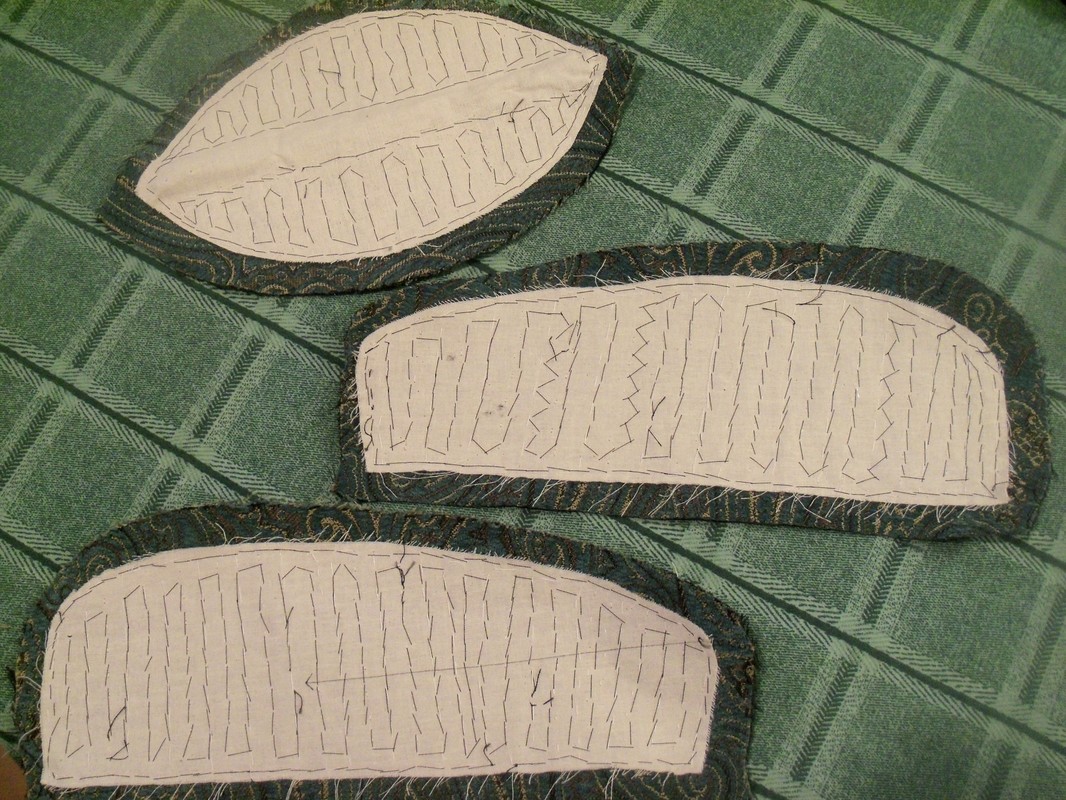

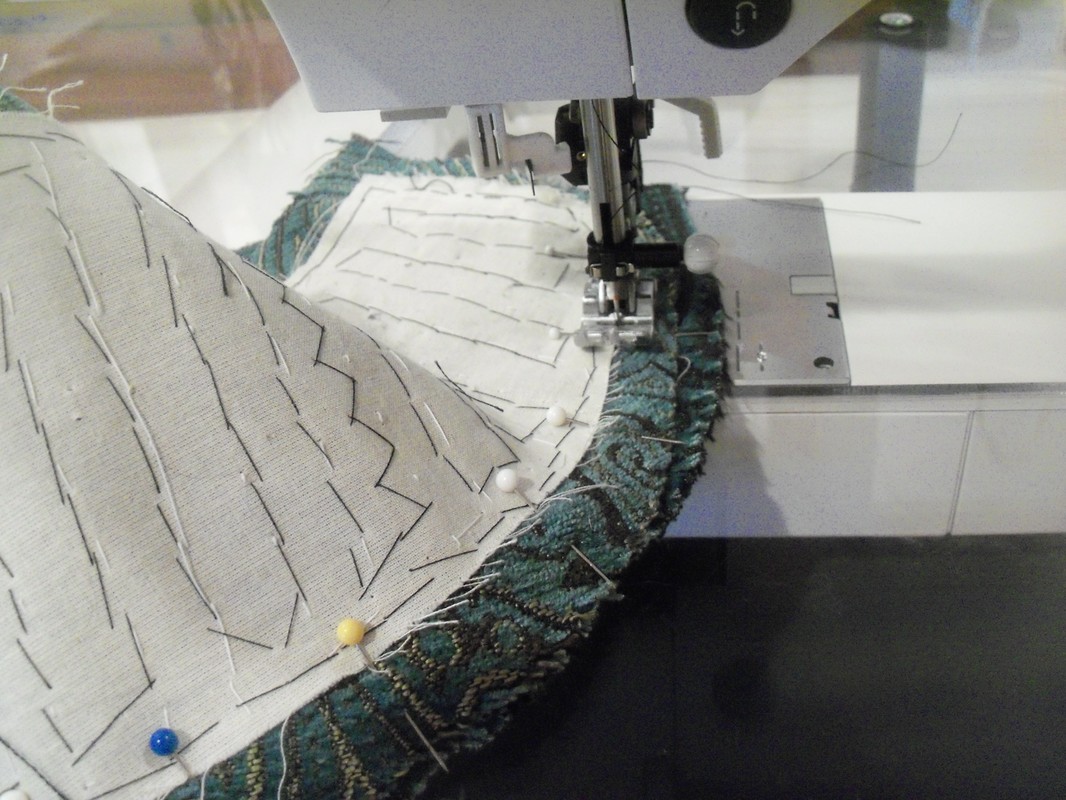

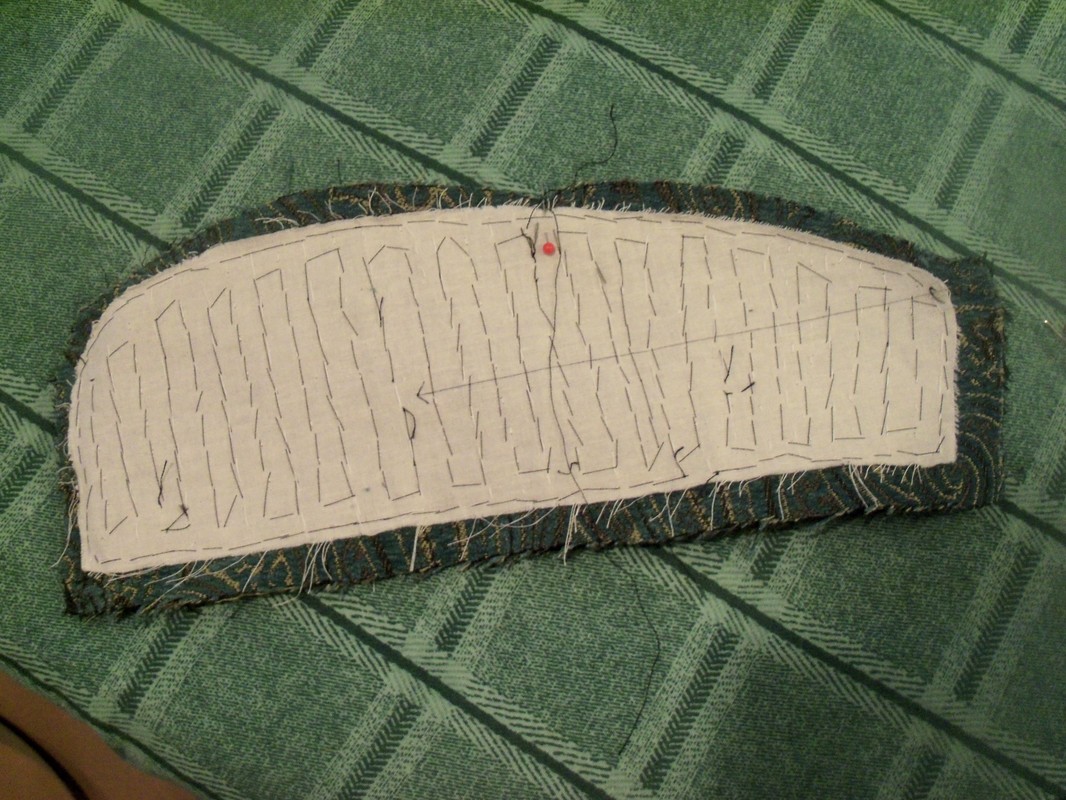

Passing the Scottish Country Shop one day, I went in to see if I could examine a Glengarry cap in person. Alas, I didn't have much time before they closed, but based on what I saw there, I have made some alterations to my pattern. For instance, it's clear from the tartan caps like this that the base of the pattern is not a straight line, but a curve. If you turned the cap so that grain and cross-grain are a plus sign (look at the plaid), the back of the hat is hanging down. Another thing which is clear when I contrast my finished hat with the picture at the top of the post is that I should not have sewn around the curve at the bottom of the hat... the authentic hat is not sewn around the curve, so the curved edges flair open around the head when worn, and fold neatly when not worn. Here's a little sketch of the revised shapes: THE IROQUOIS CONNECTION Continuing research on the Glengarry cap led me to more information on the Iroquois beadwork which had so puzzled me at first. According to Gerry Biron, in his exhibit Made of Thunder, Made of Glass, plain blocked-wool Glengarry caps were made for export to North America, and then decorated by the natives: The Glengarry bonnet was a hat style adopted by the Scottish Highlanders around 1800. Nineteenth century Hudson Bay Company trade invoices indicate that large quantities of these were imported for the Indian trade. The Indians would embellish them with beads, dyed moosehair and ribbon work. Many were decorated with floral patterns but exceptional examples will have a bird or some other pictographic element in the design. Some of these may have been worn as “smoking caps.” Style-conscious men wore formal indoor caps from the sixteenth through the late nineteenth century. They were generally worn to prevent the hair from smelling of tobacco smoke. These hats, along with small bags and purses, were then sold back to Europeans and white Americans as souvenirs. Some people may think this was degrading for the Natives (selling off their culture) or cultural appropriation for the whites (wearing someone else's culture), but I disagree. It's not like the souvenirs were the last relics of the tribes, irreplaceable once sold... they were produced for the purpose of sale, and their production also served to preserve and develop the traditional craft of beadwork embroidery. A living tradition is always better than a dead one; once an art form stops changing, you might as well stick it in a museum and move on. (I speak as one who has some experience in the living traditions of modern needlelace, modern English Country dance, et cetera.) There are also pictures of the hats being worn by Native Americans, which makes sense, since obviously they wouldn't have sold them all, and handwork is often very personal. So that explains the Iroquois beadwork, but why Glengarry hats and not other hats? Well, the Hudson Bay company had lots of Scottish connections, for one. And the Victorians, thanks to Queen Victoria's love of Balmoral, were all about all things Scottish. Tartans, tams, Glengarry bonnets, and other Scottish details were very much in fashion. MAKING THE NEW CAP Since I'd already cut out my sister's hat pieces, I couldn't re-cut them to have the correct angle down the back. (Note to self: Don't cut out multiples until you're sure of the pattern!). I could, however, attempt to sew it a little differently from last time, perhaps shortening the front. Here are the layers cut out and sewn together: In sewing the side to the top, I saw immediately that it wasn't going to fold flat. Check out the in-progress pic on the left and the finished pic on the right, below. So I put a red pin at the start of the "whale tail", and unsewed to that pin. This improved the shape, but made the hat so much smaller that it would become a kid's hat! I split the difference. Let me define a few points for you... look at the picture just above, on the right. We're looking at the un-pinned whale tail. Let's call the point of the almond shape (center piece) A. Now look at the side piece which is lying on the bottom, on the table. The two points of the side piece will be B (top) and C (bottom). Previously, A had been sewn to C, with B being left to flare open. For my alteration, I sewed A to almost-B instead, and trimmed C off completely! See the pic below. It folded (mostly) flat! Hurray! I finished the outside with a strip of grosgrain ribbon and a thunderbird pin. I didn't line it, because I didn't want to, and because I liked the interior view with all the hand-stitches. And so I sent it off to my sister! Waiting on pics to see how she looks in it! *Taps foot; looks at sister*

4 Comments

The Sister

9/14/2017 10:06:02 am

Well, well. I do believe I sent you pictures! (Dreadful, but I'm over it.) So I think you dropped the Update Ball. :-D I still need to find the way to wear my hat in a way that suits my personality. Thank you, my sister! <3

Reply

5/16/2019 12:06:53 am

Every thing was shown very clearly, I just Love your blog

Reply

5/17/2024 11:28:12 am

The main piece, made of tartan cloth, usually around 4 to 8 yards in length, depending on the style and the wearer's size. It's pleated at the back and usually secured around the waist with straps and buckles, known as a sporran.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed