|

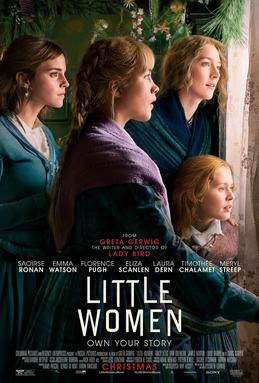

Big news in the world of sewing vloggers! Which is to say, not big news, but I am enthused. In December 2019, Sony Pictures released a new version of Little Women (Louisa May Alcott's novel about four sisters), directed by Greta Gerwig. In February 2020, at the 92nd Academy awards, the film won Best Costume Design for Jacqueline Durran's costumes.

A "FEMINIST" STORY?

Wikipedia's brief "Development History" for Little Women is interesting: In 1868, Thomas Niles, the publisher of Louisa May Alcott, recommended that she write a book about girls that would have widespread appeal.[4]:2 At first she resisted, preferring to publish a collection of her short stories. Niles pressed her to write the girls' book first, and he was aided by her father Amos Bronson Alcott, who also urged her to do so.[4]:207 Louisa confided to a friend, “I could not write a girl’s story knowing little about any but my own sisters and always preferring boys”, as quoted in Anne Boyd Rioux's Meg Jo Beth Amy, a condensed biographical account of Alcott's life and writing. So, let's break that down: two men pressure a woman to do something she doesn't want to do: write a story about and for girls. She doesn't want to because she identifies more with boys, but she caves under pressure, for money and because the publisher implied he'd publish her short stories afterward. (I wonder if he ever did?) To summarize it in the parlance of the internet: #Feminism /s Despite its mercenary origin story, I like the book, and I enjoy seeing it staged. Seven films have been made of Little Women, the first four directed by men and the latest three by women. 2009's version was directed by Greta Gerwig, and was acclaimed by critics. I have not watched it, unfortunately, so my following remarks are commentary only on the book and the YouTubers' work. I now switch to the literary present to look at each sister in turn. MEG Meg is the oldest March sister. With her mother, she manages the household. She has a job working for a wealthy family, so there's some temptation to lose her head in daydreams of being a fine lady. Though she admits to the daydreams, she always cuts herself off from taking them into reality, as when her mother buys her an umbrella that isn't fashionable enough for her fancy: her sister Jo tells her to exchange the umbrella for one she wants, but Meg say "I won't be so silly, or hurt Marmee's feelings, when she took so much pains to get my things. It's a nonsensical notion of mine, and I'm not going to give up to it." Peer pressure and money are ongoing themes in her life, and the pattern is always that she is enchanted by the glitter, gets a closer look and sees it's not gold, and backs away. She matures into a decent woman, marries a working man and settles into the role of stay-at-home mother and wife. There are two big dramas in Meg's story: the first is when she's a teenager, invited by her wealthier friends to a party. Her mom sends her off with the best dress the poorer family can manage, but when she gets to her friend's house, the wealthier girls play dress-up with her, put her in a low-cut gown, and flatter her that she looks sooooo pretty. And she is pretty. And the dress is a stunner. Of course she wants these nice things. But deep down she doesn't have the confidence to carry them off because 1) her mom's lectures on propriety are ringing in her ear, and 2) she feels like a poor girl in a rich dress. She overhears some gossip about her family and realizes her wealthy friends are vulgar in mind, and it's all humiliating. Afterward, she frames the experience as a lesson against vanity. Again, when she's an adult and a married woman, she flirts once more with the borrowed high life: her husband is not wealthy, but she goes shopping with her wealthy friend and is pressured into buying twenty-five yards of silk because it's sooooo pretty on her. This tanks the couple's budget and means her husband won't be able to afford a new overcoat that year. When she realizes what she's done, she sells the silk and replenishes the overcoat account. Another lesson against vanity, but alas only learned when she accepts her poverty as an identity. She is wrong for wanting the silk because it means not loving her husband, a "poor man". No, if he's a poor man, then she's a poor woman, and that's who they are. Poorness is framed as unalterable, and virtue is making the best of it. She does get to be very happy in her relationships, but she is happy with the understanding that she can't also indulge. Cynthia Settje from Redthreaded got the task of making a Meg-inspired costume. Early in her video, she explains her approach to the challenge: "Basically, I wanted to make her dream dress, because I feel like she deserves it." I like that approach! And the dress Cynthia gives her is graceful, womanly, and pretty without being unconventional. Unlike her sisters Jo and Amy, Meg is deeply conventional, and her battle is always to moderate her desires to what she's "allowed". This dress is perfect for her: exactly what I think Meg would have worn to a fancy party, had she the money to play those games and the sense of self to not let them play her. Cynthia's video is well-filmed and narrated, with the best demonstration I've seen yet of how cartridge pleats are made, and wonderful explanations of the inner workings of the gown. The silk is swoon-worthy in and of itself, and the whole gown is so perfect in its proportions that it makes me like an era I usually find a little too insipid in terms of women's fashion. JO The next March girl is Jo, a wildly creative and rambunctious tomboy, fervently dedicated to her writing and her dramas. Her trials in the book have to do with her inability to accept the processes of growing up: most at home in her childhood, she feels threatened by the changes that come with maturity. She hates dressing up (unless it's in a theatrical costume), hates the little social niceties she's expected to show, and has an ol-buddy-ol'-pal kind of friendship with a boy named Laurie. When her sister Beth falls ill, Jo dedicates herself to her care, and so leaves some childhood behind. As an adult, Jo wants to go to Europe, study, and publish her writings, but her stubborn, rudely-expressed independence makes her odious to people who would otherwise be her patrons, and guarantees that she'll never have an easy path to her goals. Jo is the author-insert character, and commonly a fan favorite. And, post second wave feminism, Jo ticks all the "empowerment" boxes for modern readers/viewers: she chafes at and rejects "traditional femininity", dresses like a boy, writes short stories and novels, wants to earn her own money, and chooses a difficult, uncompromising path through life. Nowadays, I find the whole "female empowerment through acting like a man" thing to be irritating. But I won't bash it too hard, for a couple reasons. First of all, because I went through that stage when I was a young girl. I read countless stories where the female protagonist disguises herself as a boy so she can have adventures. I imagined myself traipsing around Medieval England in britches, doing "everything a boy can do". And, even though child-me loved girly clothes, all the women wearing pretty clothes in books or movies were models of passivity. The truth is, girls want adventures as much as boys do, and women want to be agents in their own stories. But when we look for models of adventure and agency, those models are usually male. So it's not surprising that immature girls, looking to have significance in their world (or their imaginary world), copy men. Second, I recently become aware of my own mean-spirited and down-cutting self-talk. Knowing that the little girl I was lives on in the woman I am, I have begun arresting those thoughts with the question "Would you say that to your (seven year old) niece?" If I recoil at the thought of talking that way to my niece whom I love, then I refuse to talk that way to myself. Grown-me no longer wants to dress like a boy in order to have a speaking role in my own life, but grown-me is trying to be gentle with child-me who understandably thought it a good option. Anyway, we must not despair of Jo. Though she spends a good part of the book digging in her heels and demanding that her little family of sisters stay the same always, she comes out right in the end. As an adult, she very sensibly declines the romantic attentions of Laurie, recognizing that he's too much like a brother to be a lover to her. She moves alone to the big city, works her way to her goals, and begins contemplating romance... in the abstract. As she says to her mom: "The more I try to satisfy myself with all sorts of natural affections, the more I seem to want. I'd no idea hearts could take in so many. Mine is so elastic, it never seems full now, and I used to be quite contented with my family." So her heart is primed for love when she opens it to an older man who meets her mind-to-mind and encourages her to write with integrity instead of just for money. Rachel Maksy is the vlogger tasked with making Jo's costume. She took an interesting approach: she used all recycled materials. Re-purposing is her jam, anyway, but it's also in keeping with the March's financial situation, being in what was then known as "genteel poverty". That is to say, their means were limited, but not sunk so low as to take on "workwomen" jobs like doing other people's laundry or working as maids. Indeed, they had a maid of their own! They got by through scrimping and economizing, and still had the social standing to be invited to parties. They also benefited from the generosity of liberal wealthy patrons, like their aunts and their neighbor. Using commercial patterns, Maksy made a skirt, shirt, and waistcoat, combining these elements to make an outfit Jo might wear. BETH Beth is the next March sister. She is sweet and saintly, always doing generous things for others and making peace. She fits more into a Victorian trope--the angel-baby taken to heaven because they were too good for the world--than an actual child. And indeed, she is taken to heaven too soon. As a child, she gets Scarlet Fever (from helping a poorer family who had the disease) and nearly dies. Her health afterward is delicate, and she spends her life in the narrow sphere of the home, playing with kittens and arranging flowers, offering cheer and support to her sisters as they venture into the world, but never allowing herself to dream that she might someday leave the fold, because she knows her days are short, even though she "seldom complains and always speaks hopefully of 'being better soon'." She dedicates herself in saintly, angel-child fashion to the family, and everyone loves her. As an adult, she dies, and it's the saddest thing ever. If growing to adulthood is the theme of the novel, each sister shows us a different way: Meg matures by learning to say no to her childish fancies, but Jo with colossal bad-temper refuses to grow up or allow her sisters to do so, until she has no choice left. Jo doesn't so much step into adulthood as she watches her girlhood step away. Beth, however, is enshrined forever in girlhood... standing on the threshold of a door she cannot step through. Hers is a story of pathos, told with Victorian sentimentality. Taylor, from Dames a la Mode, imagined a happier ending for Beth. What if she didn't die young? What if she lived... frail, perhaps, but alive? What kind of dress would she wear? Something easy and not too constricting, perhaps. So she selected the Wrapper or Morning gown from Fig Leaf patterns for her costume for an imagined adult Beth. This dress is made from a soft pink silk sarsenet, which is just delicious to see in motion. It's got some basic bodice structure to hold it together, but its front is just a loose, shoulder-to-toe drapery held in place by a belt. Such a garment could be worn without a corset, or could be worn by a pregnant woman whose frame kept changing size or a housewife who wanted more range of motion while cleaning. It's comfy and practical. The video is meditative to watch because of the music, and it's nice to see how Taylor did the alterations of the bodice for her long waist and narrow back. AMY Amy, the youngest sister, has a fascinating arc. In the beginning, she's a somewhat selfish child. There's a traumatic incident where, in a fit of pique, she burns Jo's treasured book of stories, and that's a very mean, petty thing to do. But she begins to turn when Beth is ill and she's sent away to keep her safe from the fever. Alone at Aunt March's house, she labors to please and respect the old lady, and finds private solace in prayer. When Beth recovers, Amy resolves that she will no longer be selfish, but will strive to be kind and generous, like her saintly sister. On the surface, Amy and Meg seem to share an interest in wealth, but when we look closer we see that Meg's interest is always in the benefits of money--the pretty clothes and fine things--while Amy's interest is in the idea of gentility. She is always conscious that their family came down in the world from noble beginnings, and she wants to be a lady, to associate with fine people. Like Meg, she sometimes mistakes glitter for gold. She also sometimes lets practicality make her cynical in an effort to "get ahead", but ultimately, her focus is character, behavior, and mind. "Chapter 29: Calls" is my favorite chapter in the whole book because it showcases the very different philosophies of Amy and her hoyden sister Jo. Each one believes that she's acting with integrity, but their starting values are different enough that they end up in different worlds. They set out, at Amy's insistence, to pay calls. "Calling" was a social obligation of the time. It meant getting dressed up formally and visiting neighbors, for short visits, simply to show them respect. If someone called on you one week, you would call on them the next. Calls were pretty short, maybe ten or fifteen minutes, so people could do them in batches, calling on all their friends one day, and being home to receive calls another. If your neighbor was not home when you called, you could leave a calling card to say you tried, and they in turn would call on you later. It was courtesy. Jo, naturally, doesn't want to make the calls, and chooses to be a stinker about it by playing roles at each friend's house. In one place she acts stiff and haughty, in another she gossips girlishly in an unkind imitation of one of their flighty acquaintances. Amy is embarrassed, because she wants to do what is proper and has an instinct for doing what is kind. In the young ladies' conversation, Amy expresses her philosophy of manners: "Women should learn to be agreeable, particularly poor ones, for they have no other way of repaying the kindnesses they receive." It's a philosophy Jo finds abhorrent, degrading, but one which serves Amy very well. As for morality, which philosophy is better, one which hurts the feelings of others on stubborn principle, or one that promotes peace and friendliness? If a path of peace happens to have material benefits, that doesn't make it a materialistic path. Joe seems to think she has to push material advantages away, lest anyone think she kowtowed for them! The last visit of the day is to their Aunt March. Jo says that they don't need to "make a call", because they see Aunt March all the time. Amy replies that a call is different from a visit, and paying a call is a formal courtesy that shows Aunt March respect. Once in the house, Amy, though tired and frustrated, exerts herself to be pleasant, while Jo exerts herself to be rude, with the result that even the parrot tells Jo to sit and spin. Amy loves art, and, as a companion for another aunt, goes to Europe and tries her hand at being an artist in reality. She quickly sees that her talent is sufficient for her own pleasure but not brilliant enough to make a career. With real sadness but eminent practicality, she sets that dream aside and resolves to marry well and do good in the world through her other talent: sparkling in social settings. At this same time, the despondent Laurie wanders Europe pining for Jo, gets over himself and then gets over Jo, and develops feelings for Amy, who loves him back. So in the end she marries Laurie, and he has wealth enough to support her and help the less practical Marches, while Amy has the gentle good sense to inspire manliness and industry in Laurie. Together with Laurie's grandfather, they set out to be philanthropists. Angela Clayton got to do an Amy-inspired dress, and she went all out, making a "Transformation" dress, which was the 1860's version of a day-to-evening ensemble: a skirt with two bodices, one for day-wear and one for dinners and balls. Transformation dresses were common for women who traveled, because they were two outfits in one, so I like to imagine Aunt March paying for Amy to have this made before her trip to Europe. The color scheme is accurate to the novel's description of Amy: diaphanous blues. And the many carefully constructed details--the bows bound in bias tape, the rows of ruffles, the combination of fabrics--are each so artistic that I can easily see them being a delight to Amy. Angela Clayton's video, meanwhile, is an absolute marvel of useful details, clear narration, and constant inspiration. I love the bias-bound bows so much! My gosh, they are so much work... In the story of Little Women, each sister got what she allowed herself to want: for Meg, domestic bliss and duties; for Jo, the hard life and unusual rewards of going her own way; for Beth, gentle home pleasures and love; and for Amy, high society life with a loving husband who could support her in style. Their author was not so fortunate; Louisa May Alcott did not get what she wanted: a life of financial security AND artistic freedom. For money, she wrote the stories that sold, even though she resented them. That is sad.

Yet her work has a happy legacy: generations of readers have loved the Marches, and identified with the girls. I think I vacillate between feeling like a Meg and feeling like an Amy, but I hope I am bold enough, self-assured enough, to be Amy in the end. Which sister do you feel like? The YouTubers who made the Little Women costumes each did a wonderful job, and inspire me. Well done all! Marvelous work!

2 Comments

The Sister

4/23/2020 10:31:00 am

Well well, that was delightful! I loved this post, Karen! You're so thoughtful and insightful; I love how you analyzed the characters and showed the gowns that other sewists made for them. I adore the "dream dress" for Meg, but can totally understand why each vlogger took the path they did for their assignment.

Reply

Are you aware of the "not like other girls" phenomenon? It's when women post online or talk in conversation about how they're "not like other girls" because they defy feminine expectations. The "other girls" in question are more stereotypes than reality... for instance, a woman might post a comparison pic where "other girls" are filing their nails, but she is "not like other girls", so she's driving a monster truck through a mudpit. This trend attracts ire for several reasons:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed