This will be a long post, mostly concerning the fire in 1911 and the pro-labor legislation that followed in America, but also touching on the global sweatshop problem today. Make some tea and join me for a talk.

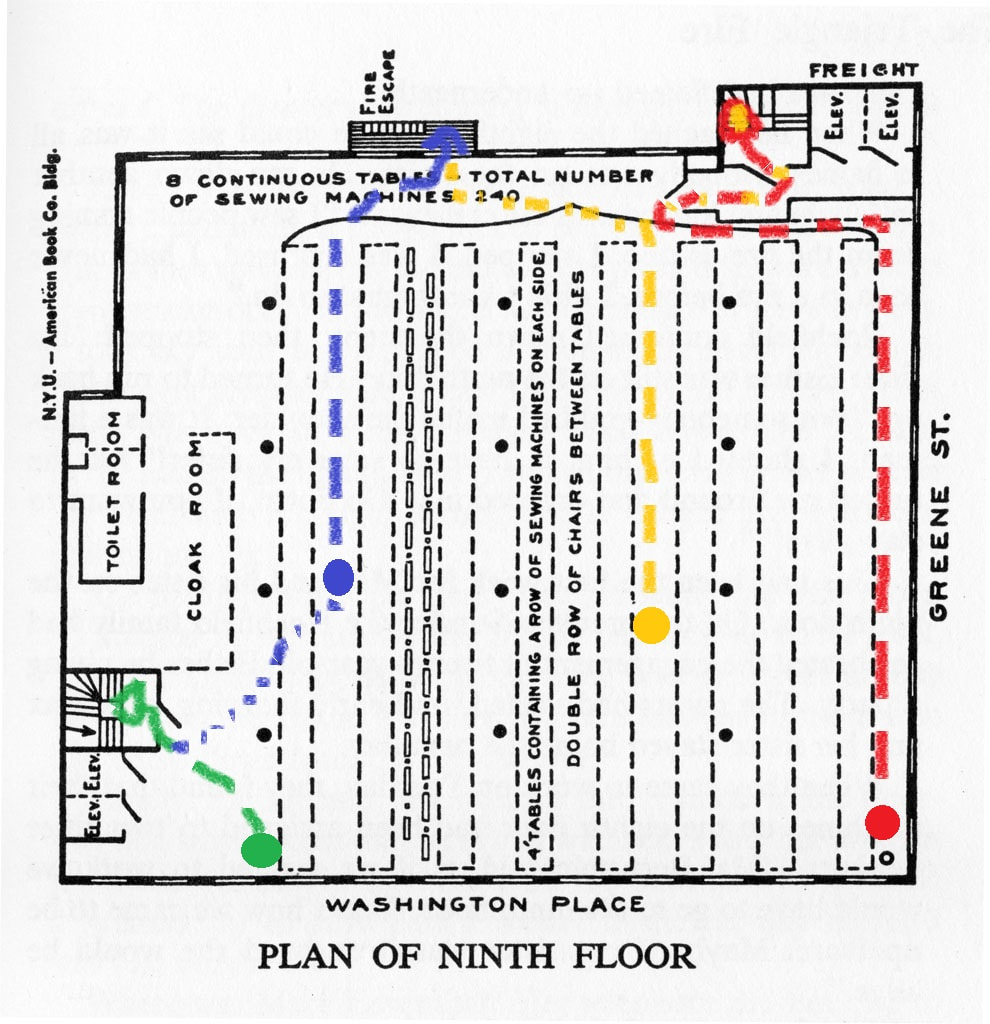

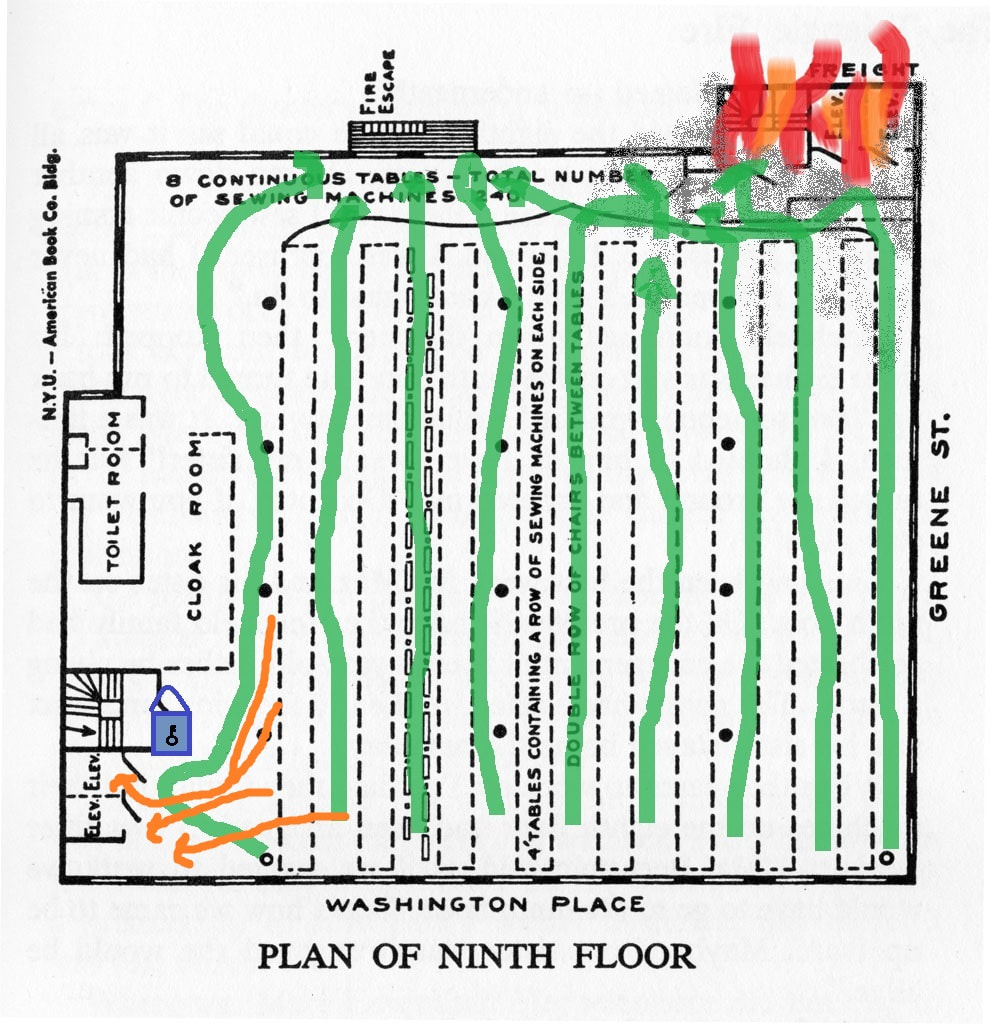

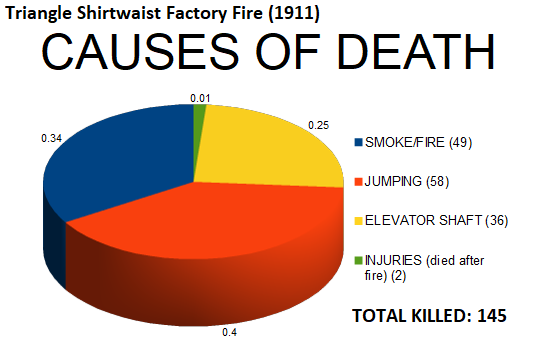

It's interesting how words shift in meaning over time. Nowadays, when we say "waist", we're talking about a horizontal line between ribcage and hips, the place where the body bends. There's some confusion about the waist's location, with men usually thinking their waist is the same as the waistband of their trousers. Women might know if they have high waists or low ones. Regardless, the mental picture of the waist is a horizontal line or measurement. In the Edwardian era, the word "waist" conjured up a more vertical image: the distance from the body's bending point upward to the shoulders, the torso. The garment which covered the torso was also called a "waist", and the vertical measurement was important when making or ordering one. This is where the term "shortwaisted" comes from. A woman with a high waist by the modern use of the word would wear a short waist by the historical use of the word. THE SHIRTWAIST KINGS Isaac Harris and Max Blanck arrived (separately) in America in the early 1890's. Both were tailors from impoverished shtetls in Europe. Harris immediately went to work in various sweatshops and learned the ins and outs of manufacturing in New York City's garment district. Blanck became a middleman, connecting makers with sellers. They met through their wives, who were cousins to each other. Together, they founded the Triangle Waist Company in 1900. They worked hard, invested their money in equipment, and laboriously built up their company to produce the ubiquitous female garment of the age: the shirtwaist. Ambitious and competitive, they embodied the American dream as it was understood at the time: anyone could, with hard work, be prosperous. But their position on the top of the shirtwaist industry was tenuous. For one thing, there were countless competitors willing to undercut them ("over 10,000 other textile manufacturers in New York City"), and their best defense was to make more clothes, and faster, so no-one could out-produce them. To that end, they invested in modern electric sewing machines to replace treadle-operated ones, so their seamstresses could sew even faster. For another thing, the shirtwaist was starting to slip out of fashion. When introduced in the 1890's, it was a marvelous innovation, but no fashion lasts forever, and the focus was shifting to colorful dresses again. How would the Triangle Waist Company move into a post-shirtwaist world of fashion? Meanwhile, every day the newspapers had news of workers on strike, workers unionizing, the labor movement. To Blanck and Harris, this must have seemed like a personal insult. Because of their hard work and risk-taking, they employed hundreds; they were job creators! Workers owed their jobs to the bosses; how could they turn around and complain? So what if the workers' lives were hard...? Harris and Blanck had a hard time too, when they were new arrivals, but they persevered and look how it paid off for them! This was the age built by industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, John Rockefeller, and Andrew Mellon, men who succeeded by (and were lauded for) building monopolies and defending their private interests ruthlessly. And sure, many of them also became philanthropists and put their names on everything from buildings and school funds to the arts-related grants that to this day sponsor public television shows; such scattering of largess is the prerogative of kings, and they were the kings of their world. But to them, and to smaller businessmen like Harris and Blanck, any attack on the rights of private business owners was an attack on the very people responsible for America's prosperity! It was an attack on America itself! Needless to say, the owners of the Triangle Waist Company eyed their workers with suspicion and dreaded any talk of unionizing. In fact, when shirtwaist makers around New York City had gone on strike the previous year, the Triangle Waist Company led the most vicious opposition: during the strikes, they paid policemen to brutalize striking workers, paid prostitutes and local toughs to harass picketers and pick fights, and lambasted smaller companies who gave in to the demands for union-only shops; after the strike was over, they gave minimal concessions to their own workers and still refused to allow unions in their shops. On a day-to-day level, too, the bosses were no friends to their employees. Blanck purposely set up their Asch building factory with tables laid out to discourage talking among workers, and with exits locked during working hours to prevent unauthorized breaks. When the women left the shop at end of day, they were searched to make sure they were not stealing any waists or fabric. WHO WERE THE WORKERS? Most of the workers were female. They were recent immigrants to the United States, speaking many different languages: Polish, Italian, Yiddish. There were family groups: mothers and daughters, sisters, et cetera. Many were children and young teenagers. They were paid about seven dollars a week, which wasn't much, and their wages were further depleted when the factory owners charged them for the electricity and needles they used, for thread they thought was "wasted", and for imperfect products. They were the kind of employers who didn’t recognize anyone working for them as a human being. You were not allowed to sing. Operators would like to have sung, because they, too, had the same thing to do, and weren’t allowed to sing. You were not allowed to talk to each other. Oh, no! They would sneak up behind you, and if you were found talking to your next colleague you were admonished. If you’d keep on, you’d be fired. If you went to the toilet, and you were there more than the forelady or foreman thought you should be, you were threatened to be laid off for a half a day, and sent home, and that meant, of course, no pay, you know? You were not allowed to use the passenger elevator, only a freight elevator. And ah, you were watched every minute of the day by the foreman, forelady. Employers would sneak behind your back. And you were not allowed to have your lunch on the fire escape in the summertime. And that door was locked. And that was proved during the investigation of the fire. They were mean people. There were two partners, Rank[sic] and Harris, and one was worse than the other. People were afraid, actually. Nevertheless, for these impoverished women, any money was good money, and the chance to be working girls and help their families was worth the hardship of laboring in bad conditions. THE FACTORY The floor plan of the 9th floor of the Asch Building allowed for 240 workers to be seated there, with two regular exits (stairs and elevators on one side of the room, and the same on the other), and one rickety fire escape that, unbeknownst to the workers, would not support their weight and did not reach lower than the second storey. Nowadays, we'd say that 240 people were too many for the space, but at the time the owners included the vertical space of the high ceilings when calculating space per person. Let's look at the floor plan in a best case scenario. The drawing is courtesy of the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, and the colored lines on it are my doodling: In a best case scenario, all the exits are operational. So let's say you're the green lady. You're wearing a corset, a floor-length gown, petticoats. You're sitting pretty close to a staircase and an elevator. You know your fire safety, so you take the stairs and get out okay. If you're the blue lady, you have a choice between going out the long way, between the rows of tables, and using the external fire escape, or climbing over the table and going out the stairwell with the green lady. The climbing option might be faster, and therefore better, but disaster analysts have found through analyzing actual behavior in emergencies that people revert to the familiar, so you might go the long way around because that's the way you came in. If you're the yellow lady, climbing over tables won't help you much, so you go down the aisle and make a decision at the end between the external fire escape and the stairs. It might not be much of a decision, though: the people behind you might push you one way or another. The worst place belongs to the unfortunate red lady: even in a best case scenario, you're still trapped in a corner, and getting out means pushing through a bottleneck. Obviously, the layout of the tables is a nightmare. The aisles all run parallel to Greene Street, channeling people toward the freight elevator and fire escape, with no cross-aisles leading to the alternate exits. There are no spaces between the tables and the Washington Place wall, so people can't walk out that way, either. Now compound the situation with the fact that there are chairs, sewing machines, people's bags, piles of junk on the floor, fabric soaked in machine drippings, and hallways lined with wicker baskets of fabric and jugs of oil for the sewing machines. Your co-workers include children and people whose languages you don't understand. And none of you ever did a fire drill or got any preparation for this. It's no wonder that in the shirtwaist workers' strike the previous year, unsafe working conditions were a big complaint! And while other factories in the city had to clean up their act when they let unions in, the Triangle Waist Company didn't unionize and made no improvements. ACCIDENTAL SPARKS The Triangle Waist Company occupied three floors of the Asch building: cutters on the eighth floor, seamstresses on the ninth, and the executive offices on the tenth. The fire began at 4:40 on the eighth floor. Smoke was spotted outside within five minutes, and the fire department was called. The approximately two hundred fifty people on the eighth floor all escaped, but not before someone called up to the tenth to warn the executives, who escaped to the roof. But there was no phone and no alarm for the ninth floor workers, so their first warning of the fire was when smoke and flames came up through the Greene Street stairwell. Though certain YouTube trolls like to suggest arson was the cause of the fire--either arson by the owners to collect insurance money since they knew their shirtwaists were going out of style, or arson by union organizers trying to prove how bad conditions were--there is no evidence of arson in this case, and no-one seriously suspected it either then or now. It's worth noting that the fire started on the eighth floor while the Harris and Blanck were on the tenth. Not only that, but they had brought their children to work that day. It would be insane for them to start a conflagration that might kill themselves and their loved ones just to get insurance money. As for union organizers, why would they target the very people they were passionately trying to help? Since the cutters on the eighth floor were known to smoke cigarettes, even though it was against the rules, a stray spark or carelessly disposed cigarette is the likeliest cause of the fire. Unfortunately for the ninth floor workers, they did not have the best case scenario I drew above. For one thing, the factory was even more crowded than the plan for it shows. William L. Beers, a fire marshal interviewed after the fire, reported that there were actually 288 machines on the ninth floor (not 240), and 310 people there at the time of the fire. For another thing, the supervisors had a policy of locking the Washington Place exit door to prevent women from slipping out for unauthorized breaks or stealing shirtwaists or letting union organizers up to agitate. In the early moments of the fire, the supervisor who had the key to that door made his own escape without unlocking it, so that stairwell was unusable. The Greene Street stairwell was full of flames from the lower floor. So let's revisit the fire escape plan from before, this time with the added problems: The flames were coming from below, from the eighth floor, so some people took the counter-intuitive step of going up the Greene Street stairwell to the tenth floor, and thence escaping to the roof. NYU students in the neighboring building bridged the gap between the two roofs with ladders and many were saved by crawling across. That's how the tenth floor people evacuated the building. But for the ninth floor workers, that path of escape was blocked within three minutes, and then the Greene Street stairwell was entirely out of commission. Others went for the elevators. None of the sources I've read specify which elevators they took, but Pauline Newman (interview here) does mention that normally workers were barred from the passenger elevators, and used the freight elevators instead, so perhaps they tried to use them during the fire, too, out of habit. On the other hand, the freight elevators were right next to the burning stairwell, and human instinct is to run away from fire. Moreover, several sources I read specify that the elevators used during the fire couldn't hold a lot of people and had to make multiple trips, which sounds more like passenger elevators. So I'm imagining a woman in a burning building, running away from smoke and flames on the Green Street side of the building toward the stairwell on the Washington Place side. Finding the stairs locked, she'd then try the passenger elevators which were right there. I could be wrong, but based on my understanding of things at this moment, I've assumed they used the passenger elevators and drawn that escape route in orange. The elevator operators were heroic: Gaspar Mortillalo and Joseph Zito traveled up and down several times to get passengers, even though the panicking people crushed in so tightly that the doors wouldn't close. After the elevators went down, desperate people prised the elevator doors open and jumped into the shaft, or tried to climb down on the cable, but were pushed or fell. Some died falling many storeys onto the top of the car. When the heat of the fire warped the metal mechanisms of his elevator, Mortillalo had to stop his work. Zito had to stop when his car buckled from people falling on it. Many people tried to escape by the external fire escape. That was a shoddy thing tacked on the outside of the building to get around the building codes that required the factory to have three exits. The iron was not strong or well attached, and couldn't bear the weight of more than several people. It was, according to Fire Marshal William Beers, "Too small and too light, and the iron shutters on the outside of the building when opened would have obstructed the egress of the people passing between the stairway and the platform." In the heat of the fire, and under the weight of the escaping workers, the thing twisted free and dropped about twenty people to their deaths a hundred feet below. By now the conflagration was roaring through the sewing factory: there were shirtwaists, piles of fabric, wooden tables, sewing machine oil, and lint everywhere. Even the air was thick with lint and could catch fire. Outside, the fire brigade had arrived with ladders... ladders that only reached to the sixth floor. They also had nets to catch jumpers, but those there not meant to take the force of people falling from so high, and when multiple women jumped at once, the nets tore. For the majority of workers, there was now a grisly choice and only minutes to make it: stay and die in the fire, or jump out a window and die of the fall. And jump they did. In the smoke and terror, the windows were the natural place to run, and once there, what could they do? The falls were long and ended in heavy thuds on the sidewalk, or impalement on a metal fence. The first to jump was a man. Another man was seen chivalrously helping women climb up so they could jump. However, most jumpers--indeed, most victims--were women. The rain of bodies crushed the fire hoses and impeded the firefighters' work. Here's a harrowing eyewitness account. Though it was written many years after the event, you can tell the images are indelible in his memory: . . . the Asch Building at the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street was ablaze. When we arrived at the scene, the police had thrown up a cordon around the area and the firemen were helplessly fighting the blaze. The eighth, ninth, and tenth stories of the building were now an enormous roaring cornice of flames. The whole thing happened so quickly, it's hard to believe. Within twenty minutes it was all over but the clean-up and the mourning. Bodies were picked up off the sidewalk. Firefighters pushed their way into the building, forcing open doors that opened inward and were blocked from within by piles of burnt bodies. Charred lumps of once-human clay were carefully lowered from windows, with helpers standing inside the windows along the bodies' path to keep them from bumping and scraping on the walls on their way down. Policemen reported being shaken to recognize among the dead the same women they'd arrested the year before during the shirtwaist makers' strike. The emotional toll was so high that there needed to be constant shift changes as the men dealing with the dead couldn't bear it for more than an hour. The dead were brought to a makeshift morgue at the Charities Pier, and grieving family went there to try to identify people by jewelry, shoes, or the way their hair was braided. Many faces were beyond recognition, and the work of identifying people progressed partly by process of elimination (who was alive/identified already) and family reports of who was missing. Six victims were buried without names, and only the far more recent work of historian and genealogist Michael Hirsch gives them names, a century after their deaths. STATS Of the 310 people William Beers reported being on the ninth floor at the time of the fire, either one hundred forty-five or one hundred forty-six, about 47%, died. (Most recent research now says 146, but when I looked for accurate breakdowns of how people died, I kept getting 145, perhaps because the breakdowns were based on older research). Twenty three were men; the rest were women. The one-person discrepancy between the sources was probably a woman, since men were better documented at the time. What was a woman more or less... except to her family? That rough breakdown is inexact; many women would have been crushed to death in the press against the closed doors, but as they burned eventually they were listed as fire deaths. AFTERMATHShocked grief was the first response, but outrage soon followed. A crowd of 400,000 watched the funeral procession, which was filled with mourners, protesters, unionizers, et cetera. Politicians who had previously been indifferent to the cause of Labor, or opposed it because of pressure from wealthy businessmen, now found they could ride the Labor wave to more votes and power. Two years after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, a New York commission investigating factory conditions around the city exposed terrible truths, and this led to thirty new laws, covering topics like fire safety, child labor, maximum hours, and minimum wages. That trend continued. THE LAWS WE HAVE NOW The system of entirely private industry, unregulated or checked by public policy, did not continue. Regulations were passed so that even private business owners had to answer to the government for how they treated workers. Exactly what the striking workers had wanted and the business owners feared became a reality... a reality that I live in today, as an American worker. This is not an exhaustive list. Laws vary by jurisdiction, but these are the common ones we have today:

EXPORTING THE PROBLEM While it's tempting to look at the history of labor laws in the US and say that we've improved since 1911, and that workplaces are safer, people less greedy, and the overall trajectory for the human race upward, that's only a portion of the picture. In the past few decades, something called "fast fashion" has taken root in the global economy. While fashion designers used to produce two to four collections a year (synched with the seasons), clothing retailers now produce 52 "collections" a year, completely changing their store inventory every week. This caters to shopaholics who always want to see something new. Instead of thinking "Oh, I'll go to Woolworth's for my clothes this year," people think "Oh, I'll go to Forever 21 today and see what's new." Fast fashion stores strive to be a destination, an experience, an addiction, but in order to do so, they must provide constant novelty. Why would anyone go to H&M every week if the clothes were the same every time? The impact of fast fashion is disastrous. Made super-cheap and on a time crunch, the clothes are not engineered to last. This contributes to people shopping more, because what they buy doesn't work for their bodies, doesn't stand up to laundering, or doesn't fit right. As for the environment: the waste of resources, the damage to ecosystems, and the damage to farmers is horrifying. And for the workers who make the clothes... the story is the same I've just told you above. When a fast fashion retailer like WalMart tells its manufacturing company that they want a t-shirt that will retail for $6.97, they have to underpay the people who grow the cotton, the people who make the jersey, the seamstresses who sew the shirt, et cetera. Obviously, it's impossible to make a shirt for that cost in the US, with our labor laws protecting workers. But overseas? Those workers have no protection. Emphasis on low cost and high profit in an environment of few or no worker rights leads to the same kind of disasters in the developing world as New York City saw in 1911: Bangladesh's Dhaka district has seen a disastrous garment factory fire and a building collapse, for instance, with depressingly similar accounts of employers locking employees inside and disregarding safety concerns. Of course, retailers will loudly proclaim that they do not work with those factories... and they are technically right: they work with middlemen who subcontract with those factories so that the retailers can pretend they have nothing to do with labor abuses. So America didn't solve its sweatshop problem, it exported it. IDEAS UNDERLAY EVERYTHING There are lots of ideas to deconstruct here. One is the common refrain nowadays, usually spoken by pro-business advocates who oppose pro-worker regulations, that "What's good for business is good for everybody", or "a rising tide lifts all boats". Yet we know that overworking and underpaying workers is "good for business"--that's why companies do it--and it's definitely not good for everybody. All creatures inherently strive to exist and thrive. And when they are threatened, they become selfish. That accounts for the behavior of people and companies, which are, after all, creations of people. The Triangle Waist Company wanted to exist and thrive, so it cut costs and policed its workers and locked them in to keep its goods safe. That makes sense. The workers wanted to exist and thrive, so they took bad jobs when those were their only options. And when they were barricaded in a burning building, they pushed and shoved and clawed their way out if they could. That makes sense. The logical next question is whose rights trump whose? How much protection do businesses get and how much the workers? Businesses, as useful and necessary as they are, are not people. They don't have souls or lives or families. So when the business' bottom line endangers worker lives, the workers' rights must take precedence. Of course businesses always promise that they'll self-regulate, that they'll police themselves and inspect their own factories for safety, et cetera, but when human rights and company profits clash, we see workplace abuses and disasters. I'm not trying to vilify all companies, truly, but even when there's no ill will from the company, safety measures can easily get neglected when times get tough. That's why we have labor laws! That's why we need them around the world. TAKEAWAYS The most practical lessons I take from this:

BIBLIOGRAPHY Beers, William L. Transcript of his testimony before the Factory Investigation Commission. State of New York, Preliminary Report of the Factory Investigating Commission, 1912, Vol. II (Albany: The Argus Company, Printers, 1912). Republished by permission by HISTORY MATTERS - The U.S. Survey Course on the Web: "No Way Out: Two New York City Firemen Testify about the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." Accessed 9/8/2018: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/57 "Final Six Victims Identified in 2011." Remembering the 1911 Triangle Factory Fire. Kheel Center for Labor- Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. © 2018 Cornell University. Accessed 9/1/2018: http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/victimsWitnesses/victimsList.html Newman, Pauline. Interview by Joan Morrison. American Mosaic: The Immigrant Experience in the Words of Those Who Lived It, by Joan Morrison and Charlotte Fox Zabusky. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980, 1993. Republished by permission by HISTORY MATTERS - The U.S. Survey Course on the Web: “Working for the Triangle Shirtwaist Company." Accessed 9/8/2018: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/178/ "Plan of the Ninth Floor" (line drawing). Colored lines added by me. ILGWU. Leon Stein papers. 5780/087. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. Used by permission. “Shirtwaist Kings.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 2011. Accessed 9/3/2018: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/shirtwaist-kings/ Sweeney, Deborah. “Fashion Moments – The Shirtwaist.” Genealogy Lady, 30 May 2015. Accessed 9/5/2018: https://genealogylady.net/2015/05/30/fashion-moments-the-shirtwaist/ "Victims List." Remembering the 1911 Triangle Factory Fire. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. © 2018 Cornell University. Accessed 9/1/2018: http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/victimsWitnesses/victimsList.html Waldman, Louis. Labor Lawyer. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1944; pp. 32-33. FURTHER INFO Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: A chronicle of a tragic fire that occurred at New York City's Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911.

The American Experience: the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire 1911. Excerpt from "New York: A Documentary film," PBS, 1999. The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal (1979). A feature film. This YouTube video is screwy in its continuity, and the movie's cast is very small, which fails, I think to capture the size of the disaster. Triangle Shirt Waist Factory Fire: Lessons From The Ashes. Richard French Live. For thoughts on the global sweatshop economy today, watch the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: The Race to the Bottom.

2 Comments

Michelle M Harrison

3/25/2019 07:45:56 am

WHEW! I'm glad I was up early today! That was some impressive research. Did you ever read ASHES OF ROSES by MJ Auch? It was one a librarian recommended during a book talk to my middle school students. I think I might go seek it out, but after your well-written piece, I think the novel will read a little thin.

Reply

The Sister

3/25/2019 11:46:02 am

Well, that was very interesting. You and I discussed the Great Fire of London during your last visit, and you sent on some YouTube videos which I haven't yet watched. (But they're in my inbox!) This was a very tragic thing; I can't imagine the horror. And it's thanks to incidents such as this that we shake our modern-day heads in shock that a boss would lock the egress doors to disallow unauthorized breaks. Yikes.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed