Most pictures in this post are the property of Tineke Stoffels of the Netherlands. Please do check out her website! The other images are credited and linked to their Wikimedia Commons source-pages. INTERVIEWHi Ms. Stoffels! I'm very excited to talk to you about your artwork! Thank you for your kind words about my work and this series. The photographs make a strong impression--both historical and modern. I’m inspired by the works from the 17th Century, the Dutch Golden Age. But I don’t want to ‘duplicate’ these paintings. I like to add the same feeling, mood and use the same light in my work with my own subjects and themes. You're not the only photographer inspired by the portraiture of the Dutch Golden Age. When I searched for "Dutch masters portraits", a good number of the image results were modern photography, like Hendrik Kerstans' portraits of his daughter, Jenny Boot's edgy art-shots, Maxine Helfman's ruminations on race and status markers, and Bill Gekas’ portraits of his daughter. Why do you think so many photographers are fascinated by the paintings of the 1600's? I can’t speak for others, but for me it is something from my childhood. My aunt took me to the National museum when I was 12 and to this day I still feel how deeply impressed I was. The colors, the textures, the mood, the contrast between light and dark, the expression on the faces of the models, their clothing. It was a very emotional feeling, much more than looking at a masterpiece or how skilled the painter was. It was almost as if I could feel what the artist did, what he saw and how he used his paint and brushes. You are also inspired by the textiles. Your introduction to your work struck a chord with me; you write that you've photographed the collars "as a tribute to the amazing skills, the patience and the incredible amount of time it took to make such a piece of art." I’ve been always very interested in working with textiles and natural fibers. I’ve experimented a lot with different techniques: knitting, crocheting, weaving, spinning, dyeing wool with plants, embroidery, sewing, quilting, lacemaking. Let's talk about your process of making these images. To start with, the collars. I adore the lace collars in this series. Where did you get them? Do you know how old they are or where they came from? The idea for making this series started with two collars I found in 2014 at a flea market in the little village where I live. We’ve moved from the Netherlands to France five years ago, and are living in the countryside of Provence. I love to visit the vide-greniers (literally ‘empty attics’) to look for antique French linen amongst other items for my still life and portrait photography and interior decoration. Pillow covers, sheets, dishcloths, Provençal pottery, tins, kitchen utensils. Since then I’ve collected more collars. They must be hand made in cotton or linen and at least 50 years old. I know nothing about their age or where they came from. I did some research on the internet to see if I could find some information about the techniques used to make these collars. I’m still collecting collars, but they are difficult to find. It’s an ongoing process. Do you collect other things? I’ve also started to collect old linen ‘chemises’ (undergarments) to make a new series. They are from the 19th century or older. As an American, I can only imagine what amazing antiques could be found in a European flea market! Our country is new by contrast, and we rarely find things older than a couple hundred years for sale here. What's the oldest or most interesting thing you've found at a market? The oldest object for my still life photography I’ve found so far is a green glass jug, used to pour olive oil, from the first half of the 18th century. Back to the image-making process... You've got these amazing collars; next up are the models. How do you select models for the pictures? Were you going for a certain "look"? The girls I choose to model for me must have a certain look. Can’t explain what it is, but it must be an interesting face and I need to feel a connection. What about the clothing? How did the models enjoy wearing the collars? I’ve bought simple plain black t-shirts for the models to wear under the collars to make this series. No additions, no makeup, the focus is on the collar and the girl. I don’t think they particularly love the collars, but they find it all very interesting to model and to be photographed for me since they are not professional models. I once read somewhere that detail without focus is clutter. Yet artists love detail, and want to celebrate it! For these pictures, did you ever consider adding other details, perhaps staging the scene with furniture or fruit or props? How do you decide what to use and what to cut? In my work I’m looking for simplicity. I like to arrange objects and take away everything that distract as much as possible. It takes ages to get this result, I can move an object or let the model turn her face just a centimeter forward, back, to the left or right until I’m pleased. Obviously, as the final pictures show, your ultimate vision is to spotlight the girls and the collars! Once the photos are taken, you use Photoshop to edit them? How is the painterly effect achieved? I always use a neutral gray background in my studio and remove it later from the photo on my computer with a software program used by photographers, and replace it with a background I’ve created myself . I have my digital toolkit and developed my own process to get that specific painterly look, this can take days and sometimes weeks before I’m pleased with the result. The result is beautiful! I feel that you've made a tribute to the old paintings and shown appreciation for the lives of the people who made and wore the collars first. Your photographs become part of the story of the items. Thank you for your insight into your art! CLOSE-UPS: THE BODICE The first item to look at is the bodice, or "waist". In the Belle Époque (or Gilded Age, or Edwardian period, depending on what country you were in), the garment which covered the torso was called a "waist". In the early days of ready-to-wear clothing, a woman needed to know whether to order a short waist or a long one: if her horizontal waistline was set higher than average, then the vertical measure of the garment would be short and vice versa. Nowadays, we call torso coverings shirts or blouses or tops, but the old-fashioned use of "waist" lingers, fossilized, in a few other English phrases: a man's vest, for instance, can still be called a "waistcoat", and a woman with a high waistline may still describe herself as "short-waisted". Even as the more extreme "pigeon-breast" look passed out of fashion, many women still padded their bosoms with ruffly undershirts and tucked their shirtwaists in with a looser poof at the center front. Because shirtwaists were tucked into skirts at the waist, they didn't need to be perfectly fitted to the body the way earlier Victorian bodices did. This made them ideal for mass production. A New York Fire Marshall reporting on a shirtwaist factory fire described mass production this way: . . . the fire occurred on the eighth floor on the Greene street side, under a cutting table, which table was enclosed, and that contained the waste material as cut from this lawn that was used to make up the waists. They were in the habit of cutting about 160 to 180 thicknesses of lawn at one time; that formed quite a lot of waste, which was placed under the cutting tables, as it had a commercial value of about seven cents a pound. "Lawn" is a very fine, sheer cotton. (Sheer and fine enough that cutters could cut over a hundred layers at a time using the cutting tools of the nineteen-teens!) It was often used for handkerchiefs and lingerie dresses. Sheer waists were not scandalous, because women wore undershirts called "corset covers". So what about this particular waist? It is definitely not lawn, but a heavier fabric. There is a mix of hand and machine stitching, so it could have been made in a factory and altered by the wearer, or it could have been sewn at home, using machine for the main seams and handstitching for the lacy areas. Click any of the pictures below to zoom up, and you'll see that the hand-stitches, visible as long straight lines, are used to attach different types of lace to each other and the lace to the bodice. The pin tucks, on the other hand, are sewn with tiny machine stitches.

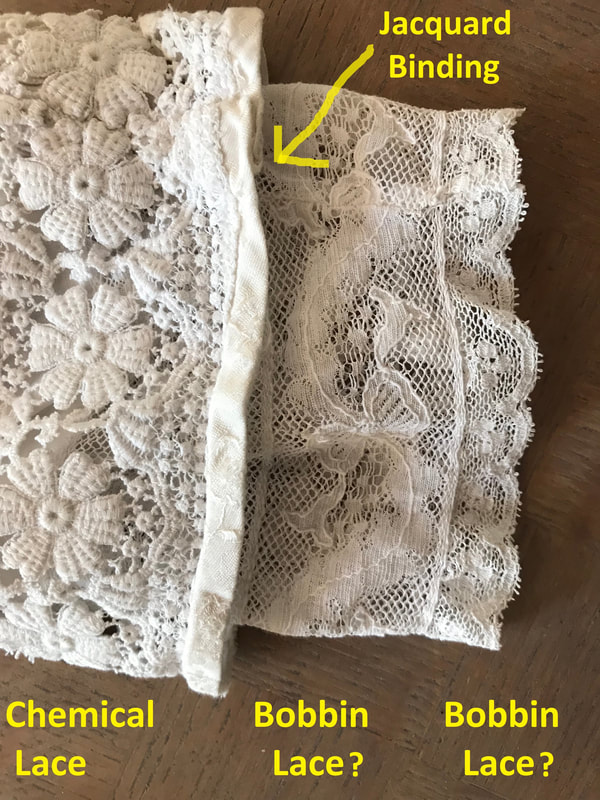

Using the charts in this resource, I realize there are three areas I need to look: the ground, the motifs (patterns), and the cordonnet/gimp (the raised outline). I'll start with the wider lace (middle in the picture above). The Ground... Right off the bat, I can rule out lace made on a Pusher machine, because that makes a six-sided ground and this lace has more like a four sided ground in a diamond shape. These threads run diagonally through the ground, with each side of the ground seeming to have two threads twisted in it, very much like bobbinet, which could be made on Heathcoat's bobbinet machine. The Motifs... Looking at the more opaque areas, I at first think I'm seeing a simple weave... over-under-over-under. The woven threads, when they come to the end of the motif, become part of the ground again. That's how bobbin lace works, and the opaque area is called clothwork. But bobbin lace clothwork does not have the regular parallel ridges I'm seeing here. These hint that I'm looking at the work of a Leavers loom, which has movable warp threads and movable bobbin threads. The movement in three planes (right and left for the warps, backwards and forwards for the bobbins) enables the threads to be twisted around each other, while for the more solid clothwork of the design the warps are held steady, producing, as on an ordinary loom, a woven effect. So the visible "ribs" are the warp threads, held stationary, while the bobbin threads go back and forth over them. These ribs are characteristic of clothwork made on a Leavers loom... that machine has parallel warp threads and zig-zagging bobbin threads. The Cordonnet/Gimp... The cordonnet looks like it's tucked under the other threads at intervals. According to the lace identification booklet, the outline on Leavers-machine lace is either needle-run when the rest of the lace is done (up to about 1850) or made at the same time as the rest (post 1841). Since this cordonnet looks like it's tucked under random threads at irregular intervals, I think it's hand-run, making this an earlier piece. I do the same analysis of the scalloped trim at the very bottom of the cuff, and think that one's a Leavers loom lace as well, though with a slightly rounder ground. It's harder to see that one, though. CLOSE-UPS: "GROS POINT"

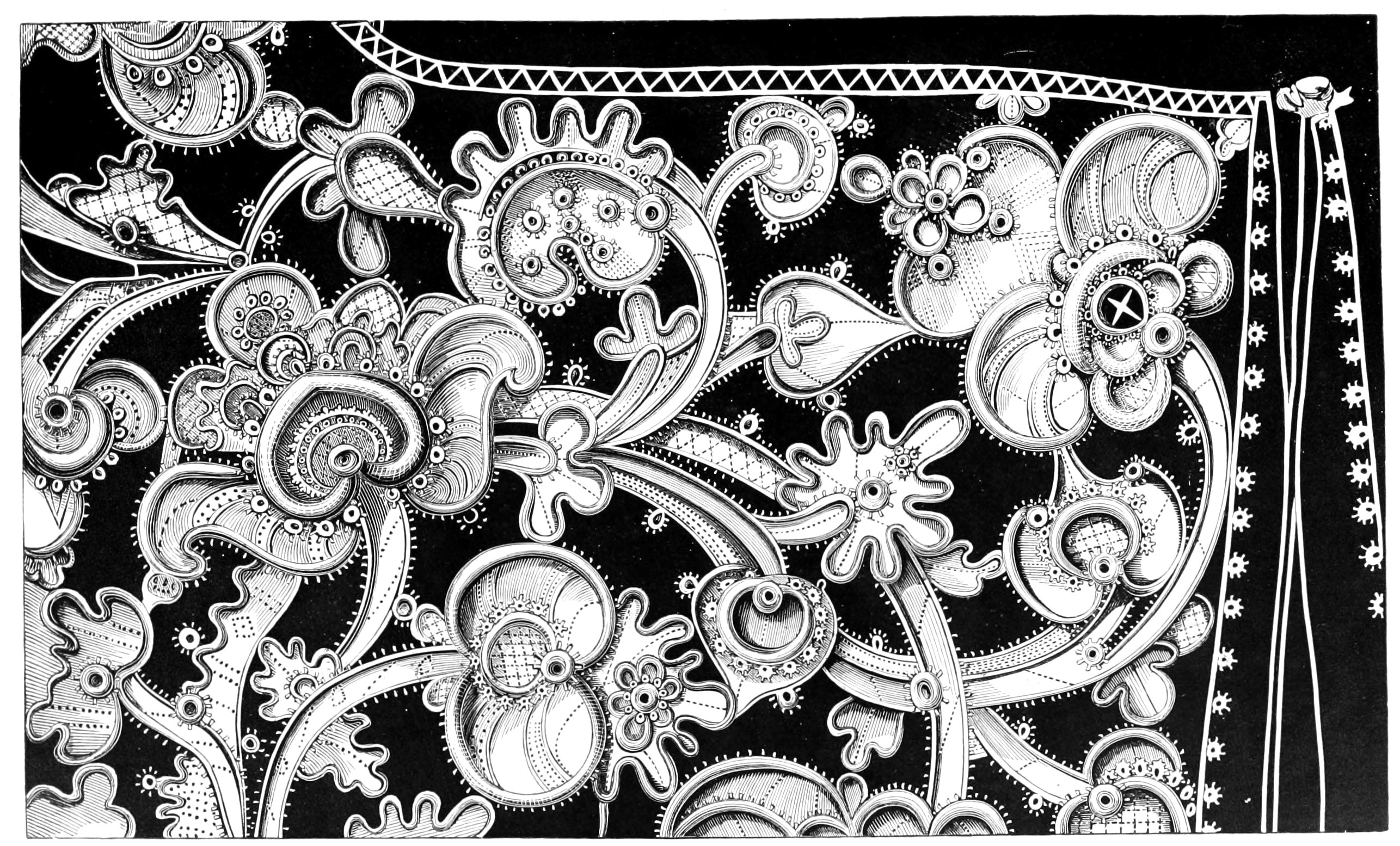

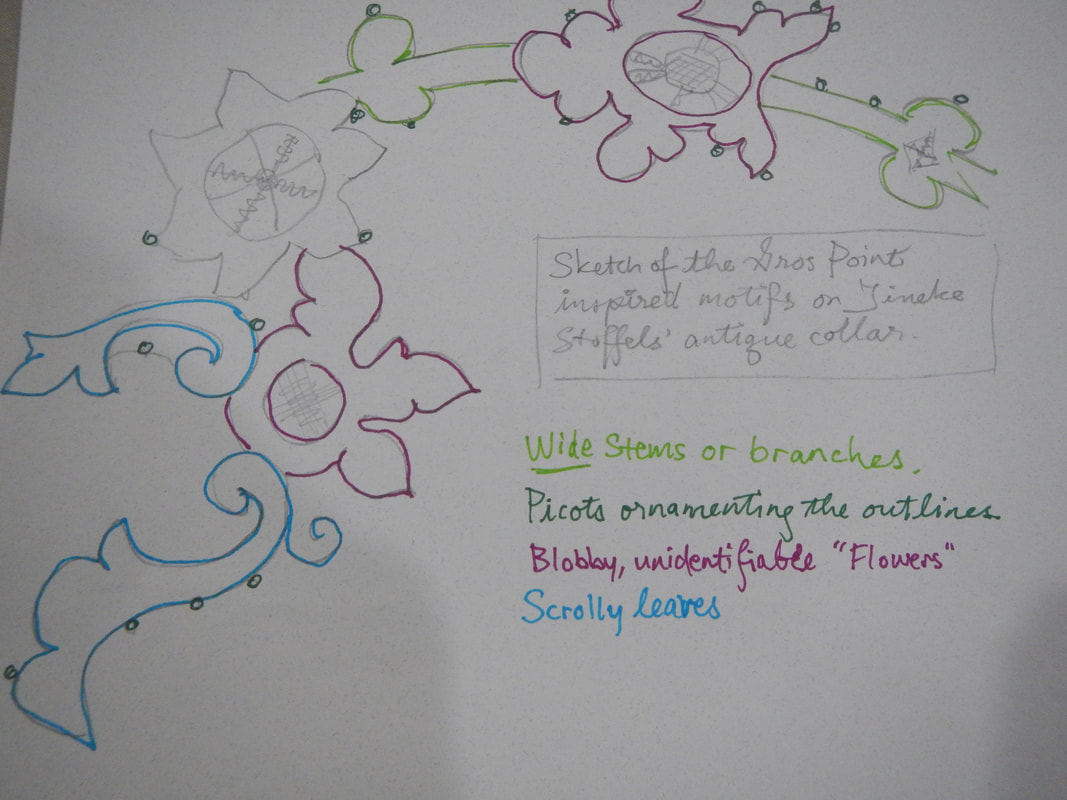

So what about this collar that Ms. Stoffels photographed? It looks like gros point and probably was inspired by it, but closer inspection shows that it's actually embroidery and cutwork on linen, one art form imitating another. Below are some excellent close-up pictures of the collar. There are three things going on here: the linen base of the collar, the applied flowers and leaves, and the cut-out areas with needlelace insertions. There is not a huge variety of stitching... mostly satin stitch, possibly stuffed or padded to get the rounded look, around the edge of the motifs, and then some wheat-ears and spiderwebs/wagon-wheels in the empty spaces. Despite that, the overall effect is stunning and intriguing. Given how badly linen wrinkles, this must have been hard to iron! The next two pictures show the front and back sides of the collar. On the front side, you can see the interior of the flowers is a more opaque white. From the back, you can see the stitches holding the flower motifs to the base. I believe this collar was inspired by gros point, and may have been meant as an homage, if not an imitation. The shapes of the leaves and flowers are very similar to gros point, from wide stems, to blobby flowers, to asymmetrical layout. It's really lovely! "MILANESE" COLLAR

Though I'm no expert on bobbin lace, I do know where to find some experts! Over on the LACEIOLI forums (IOLI is the International Organization of Lace, Inc.), I got some feedback and learned more about the construction of bobbin-made tape laces. Check out that discussion here! Many thanks, again, to Tineke Stoffels for collecting, protecting, and sharing these pieces of lace-making history! Thanks also to Lorelei Halley and the other members of LACEIOLI for sharing their expertise! I edited this post on 10/15/2018 to clarify a few points after getting their feedback. BIBLIOGRAPHYBeers, William L. Transcript of his testimony before the Factory Investigation Commission. State of New York,

Preliminary Report of the Factory Investigating Commission, 1912, Vol. II (Albany: The Argus Company, Printers, 1912). Republished by permission by HISTORY MATTERS - The U.S. Survey Course on the Web: "No Way Out: Two New York City Firemen Testify about the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." Accessed 9/9/2018: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/57 Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, New York. 1999. Reprint of A Dictionary of Lace, Second Edition. Shire Publications: Aylesbury, Bucks, England. 1984. Page 99. Farrell, Jeremy. "Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace." Dress and Textile Specialists (DATS) in partnership with the V&A: 2007. Accessed 9/29/2018: http://www.dressandtextilespecialists.org.uk/wp- content/uploads/2015/04/Lace-Booklet.pdf Stoffels, Tineke. Little White Collars: Portraits of young girls and a collection of beautiful handmade antique lace collars. Website Exhibit. Tineke Stoffels Fine art Photogaphy. Accessed 8/5/2018: https://www.tinekestoffels.eu/little-white-collars

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed