|

In September of 1666, the Great Fire of London burned for five days, reaching temperatures hot enough to melt pottery and completely cremate victims, destroying thousands of buildings, and leaving seven eighths of Londoners homeless. In addition to devastating the city, the disaster ignited religious and ethnic hatreds, stirring mobs to violence and politicians to a blame game, and threatening the newly restored monarchy. London had been a medieval town, outgrowing its own streets and buildings, but after the fire it was rebuilt, with much the same street plan, but wider streets, better sewage disposal, and fire lanes to the Thames. In 2014, PBS released a four-part miniseries dramatizing the Great Fire, which is compelling as history, drama, and costume-feast-for-the-eyes. And I... I love those things! (BRIEF) HISTORY LESSON

It was also a socially fractured age. The previous few years had seen outbreaks of plague, and the people talked of God's judgement. There was a boom in international trade, leading to enclaves of Dutch and Spanish people in the city, which made the true-blue English paranoid about foreign influence and plots, particularly the Dutch "enemies" (and of course, "they're taking our jobs"!). The King was welcomed as a relief from austerity, but his overspending was worrying to a country that had so many poor. Protestants and Catholics, Parliamentarians and Monarchists, everyone had serious convictions about how things should be run. I mentioned earlier that London was a city outgrowing itself. This showed in many ways. The population far exceeded the medieval layout, leading to overcrowding, sanitation nightmares, and so on. Tenement houses covered London Bridge. People built their upper storeys to overhang the streets, sometimes even touching their across-the street neighbors above the daily traffic. It had been made illegal to build with wattle and daub (a known fire hazard*), but people ignored that for cost reasons. The mingling of industry with residential uses (no such thing as zoning, I guess) meant that unsafe fire-practices were happening in the midst of crowded slums. Gunpowder and arms were stored around the city, too, as leftovers of the Civil War. Large crates of oil and other flammable things were stored by the docks and in industrial buildings by the river. * I should point out that wattle and daub is fire resistant when new or in good repair. The "daub" part is a mix of clay/manure/sand which hardens into an earthen wall. So even chimneys were made of the stuff, because earth doesn't burn! But it does dry up and crumble away, and when that happens it exposes the "wattle", which were sticks/twigs/grass inside the walls. Those things burn like crazy, and since they're inside every wall, once a fire starts, it can spread inside the walls of a whole house very quickly. I once saw a YouTube video showing this (I love experimental archeology!), but I can't find it now. Anyway, the wattle and daub of 1660's London was a fire hazard because it was often old and the wattle was exposed. No-one was ignorant of the fire risk, but that didn't change their behavior much. Much as, right now in Portland, everyone knows we are overdue for a massive earthquake, and there are advertisements everywhere telling us to stockpile water and food, to make an emergency plan, and to communicate with neighbors about it all... but most people don't. It makes me think of the Bible's constant refrain: "He who has ears, let him hear". Sometimes the message is loud and clear and people don't have ears. At any rate, everyone from the King down knew fire was a serious risk, but awareness of danger is not the same as intelligently minimizing it or planning for it. The fire started on Pudding Lane, in the bakery of a man named Farriner. Pudding Lane was a small section of the city filled with bakeries and cookhouses, known for its sweets. Farriner was the King's baker, not personally, but by making hardtack for the Navy. The fire started in his kitchen when he and all his house were abed. They woke to the smoke and fled upstairs, escaping out their windows. One maidservant, afraid of heights, stayed inside and died. The spread of the fire, and incompetence in fighting it ("a woman could piss it out," said the mayor when he first saw it, and many people refused to co-operate with orders to tear down houses to make a firebreak, because they didn't think they'd get repaid for their damages, knowing the king's coffers were low!), are another lengthy story. (I promised to be brief! But do go watch a documentary about it!) Meanwhile, an atmosphere of suspicion and hysteria dominated people's thoughts. Rumors spread that the fire was started on purpose by French agents, or the Dutch, or other spies/foreigners. Many foreigners were set upon in the streets and beaten to death or hanged. The Duke of York, knowing that they were likely innocent (and having Catholic sympathies himself, so wanting to protect his coreligionists), sent his men out to "arrest" foreigners, and so save them from mob violence. People became suspicious of him, when they saw that the people his men arrested were never tried or punished. After the fire, a Frenchman named Robert Hubert, who wasn't even in town at the start of it, confessed to starting it by throwing a grenade through a (non-existent) window. Hubert's story had more holes than a colander, but a scapegoat was needed. Thomas Farriner and his children signed the Bill accusing him, and three of the Farriner family were on the jury, convicting a likely insane and innocent man in order to save themselves from reprisals. Hubert was tried and executed very quickly, and after his hanging his body was torn to shreds by an angry crowd. As Elizabeth Pepys tells her husband near the end of the film, shaken as she is by the lynching of her dancing master and the ruin of her marriage: "We've strayed from ourselves, Samuel, from the people we hoped we would be." THE MINISERIES First, I want to give tribute to Rose Leslie for her acting in this film; her micro-expressions are amazing. When Lord Denton threatens her and coerces her to spy on her Catholic employer, she flinches and quivers through every interaction, her skin jumping minutely around the eyes like a horse's skin when it tries to shake off flies. I don't have any screencaps of her here because her costume is not lacy... she wears the same woolen outfit the entire time, and the only thing decorative about it is the lining of her jacket (a blue & white toile, visible in Episode 1 while she writes a letter and the camera watches over her shoulder) and the black edging to her shift (but it's too dirty to even tell if it's embroidered or a ribbon sewn on the edge or what). The King, on the other hand, is always in lace, so I have a lot of pictures of him. His expressions are limited, though: he invariably looks like he's mouth-breathing through disbelief at everything around him. He's afraid of his people--mouth-breathing. He lets Samuel Pepys advise him--mouth-breathing. He suspects his brother James of treason--mouth-breathing. The same face for the whole miniseries. Oh, dear. At least his costumes are pretty! While I gloried in all the lacework in the film, I was also surprised at it, because Restoration era portraits tend to be less lacey. The emphasis in portraits is usually on smooth satin and creamy white skin for the ladies and smooth satin and wigs for the men. In portraits, you see lace more often worn by men, usually as neckwear and sleeve ruffles, but the ladies always seem to be draping themselves (sometimes just barely) in satin, with little lace at all. Of course, it's never safe to assume that oil paintings represented what people actually wore. Portraits have "styles" the same as clothing does, and sometimes a more "natural" look is in, and people are painted en deshabille, in ways that they wouldn't actually have gone outside. The film does a good job of dramatizing both the fire and the paranoia and suspicion and conspiracy theories around it. It departs from fact in a few places, for dramatic reasons. For instance, Farriner's children are aged down to make them helpless. Hanna, 23 at the time of the actual fire, looks like she's maybe twelve in the film. On the other hand, Pepys being everywhere and seeing everything seems, surprisingly enough, to be true to history! He was well placed and important, but also curious and nosy, as his diary attests, and he did actually talk to the mayor and the king and townsfolk and riverboatmen. METHODOLOGY NOTES First, the picture credits. Screencaps are from the film, and are copyright whoever made the film (i.e. not me), but are used under the Fair Use Doctrine since this is not-for-pofit criticism. Click any picture to see it full size. Most of the real lace for comparison all comes from the UK based website Lace for Study, and is used by their blanket permission: I checked with them a while ago (scroll down to see my comment on March 22nd, 2018) and they said the site was set up for the purpose of research and I could use any of the pictures I wanted. Clicking those pictures will take you to the Lace for Study page they came from, so you can see more details. Second, I want to make it clear that all of the laces in the miniseries are reproductions. Several of them, in the close-up pictures, are clearly chemical lace, and other are machine-loomed. Actual lace from the 1600's is in museums, not on film sets filled with smoke and fire. Nevertheless, since this post is an exercise in identifying lace styles, and since the film asks us to suspend disbelief, and since it would be tiresome to say of every specimen that it was a machine-made replica... I will simply call the laces by the names they'd have if they were real and not costumes. Finally, I shall categorize the lace by style and talk about how laces of that type were made and whether it's plausible that they were around during the 1660's. RETICELLA

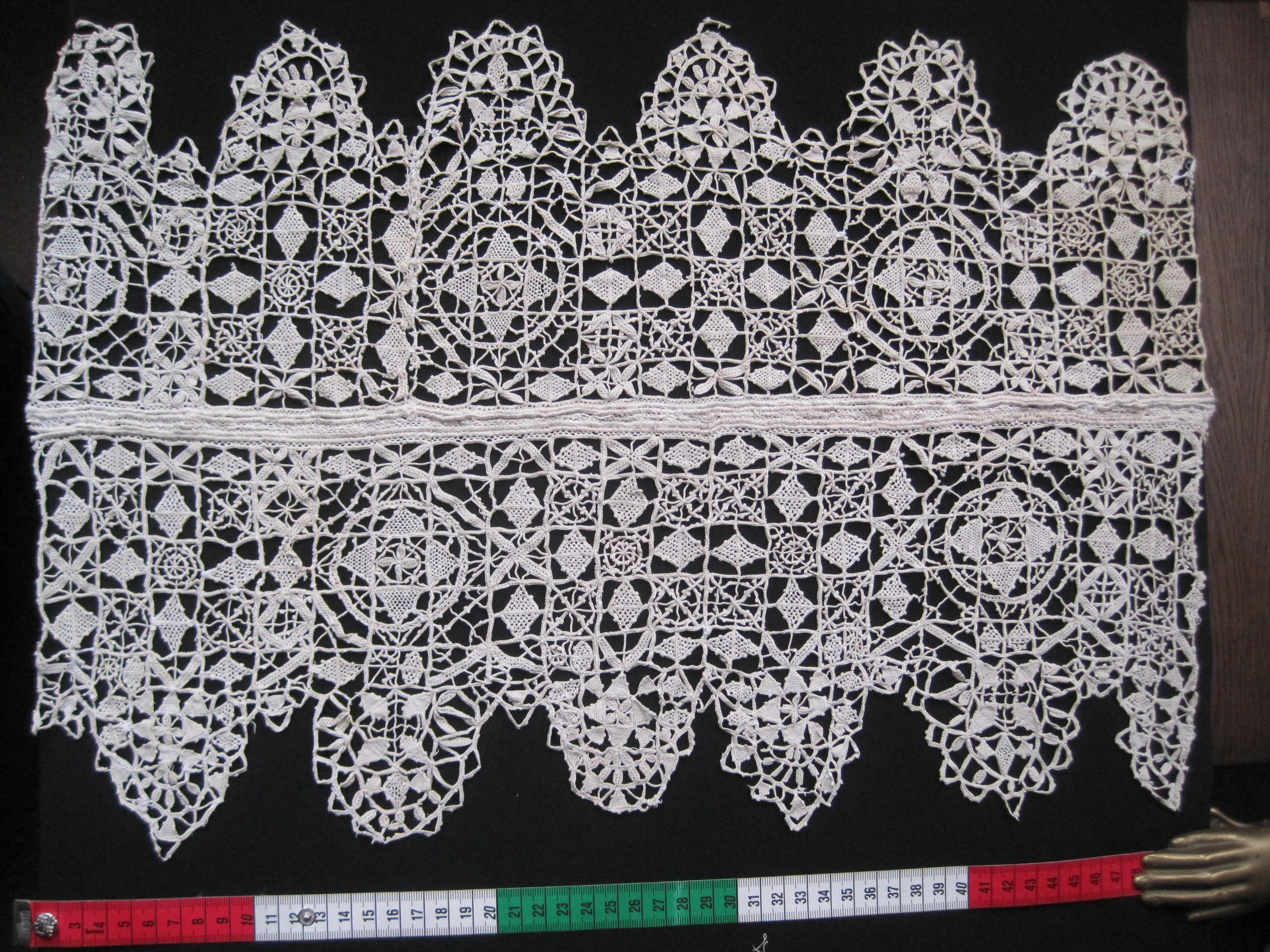

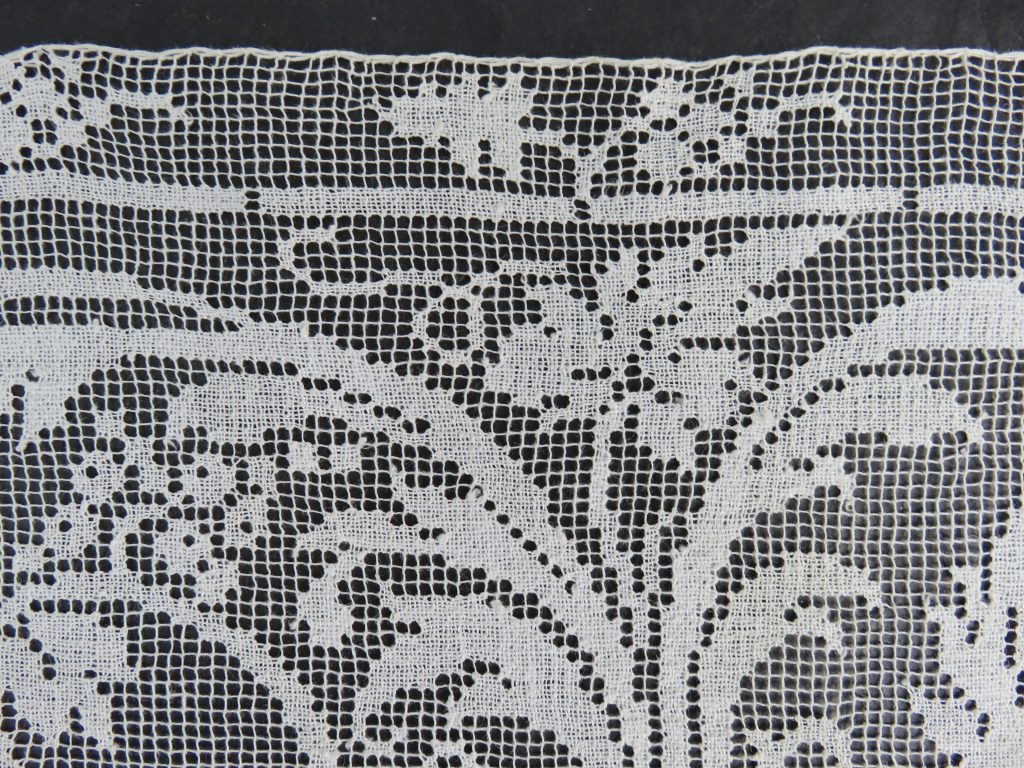

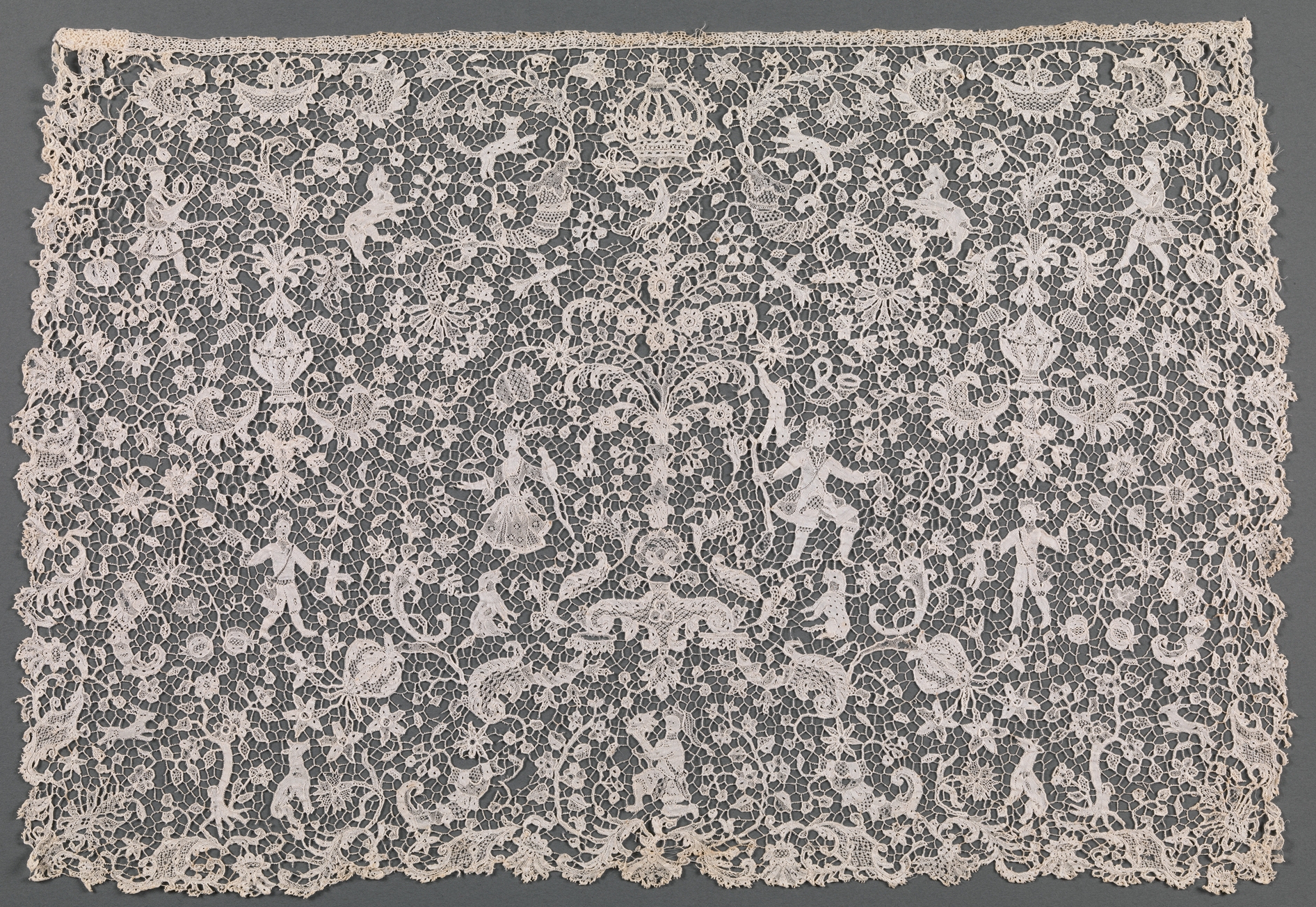

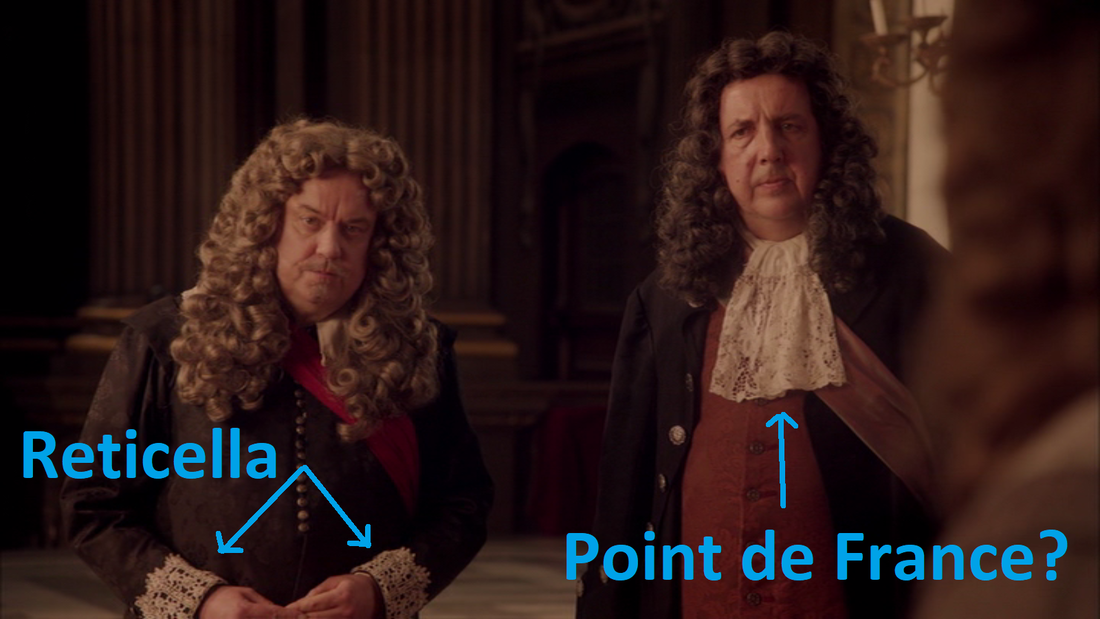

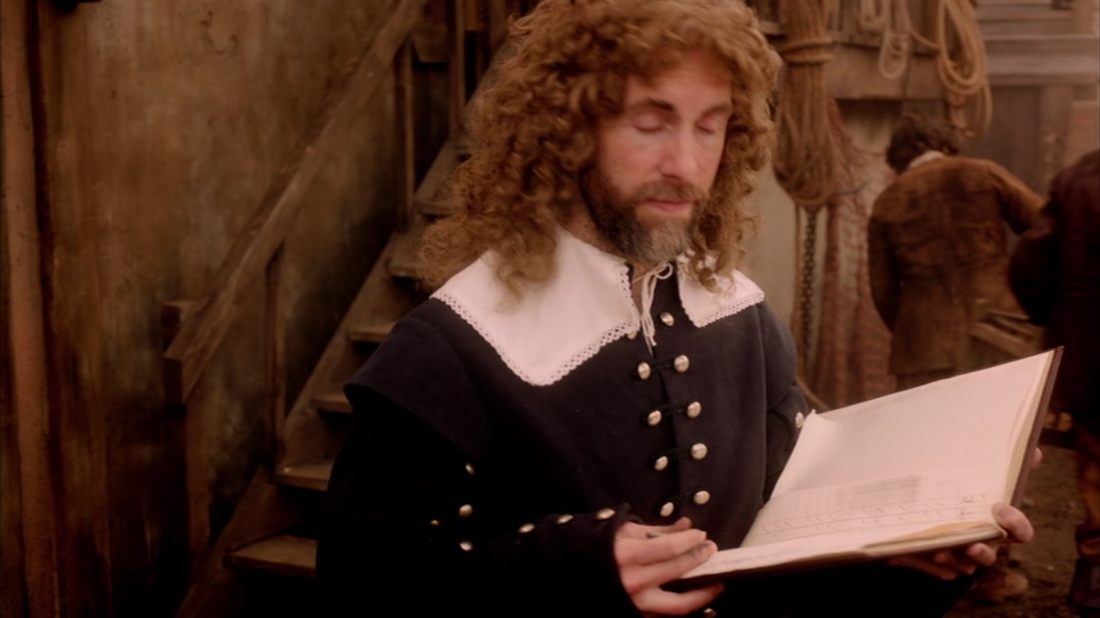

Eventually, someone who made punto antico realized that rather than pulling threads out of fabric to leave behind an empty (or mostly empty) frame, they could start with no fabric at all, and lay the framework themselves, using the embroidery stitches to hold the frame to itself. This is called punto in aria (meaning "stitch in air"), and is a true needlelace: made entirely from lace stitches with no pre-made base. In the early days of punto in aria, people continued making the geometric patterns from punto antico, and collectively the two methods are called reticella (meaning "net", roughly translated). In French, the same style of working is point coupé, or "cutwork". The reason I'd call this advisor's cuffs reticella is that they are so geometric and grid-like in their layout: stars and triangles are common shapes in that form of lace. Reticella was a common lace in the 1660's so the advisor can keep his cuffs, say I! Below is an example of real reticella, from the 1800's. We also see what might be reticella in our first glimpse of Samuel Pepys, just out of bed, in a nicely filmed scene where he and his wife converse without ever being in the same frame, and each has a wall or barrier in half their frame to signify their blocked intimacy (she has just miscarried, and he doesn't know how to comfort her, so instead frets about being late for a game with the king). Given how expensive the lace was, it's hard to imagine that anyone would go to sleep in it. Maybe a king or queen would, but I think the likes of Mr. Pepys would have a nightrail without trim, and would don his lace-trimmed shirt for the day. Here's the same shirt and lace when he's thrown his jacket on to go meet the king: GROS POINT DE VENISE In our next screencap, single-minded menace Lord Denton takes advantage of the fact that the Geneva Accords haven't been written yet to threaten a prisoner. Later he strangles the same prisoner to death, so that's... hmm... but check out his awesome gros point cravat! Gros point, the real stuff not film replicas, is another true needlelace, and is made in two or more layers, with the base layer made as needlelace, and then selected elements (flower petals, usually) made as needlelace, and stuffed edgings made as needlelace, and all sewn together to make a dimensional work of art. It was much admired and fantastically expensive. And here's an extant gros point example, from the late 1500's or early 1600's, perfectly concurrent with the era of our movie: FILET LACE? What is filet lace? Filet lace is made by first knotting a net with perfectly even square holes, then embroidering and darning to fill those holes with more thread. Imagine drawing a picture by coloring in the blocks on graph paper, or placing very large pixels on a computer, and you'll see how a squarish geometric look is inherent to this method. The larger the net, the blockier the look, but a tiny net can make a more curving look. Below is a picture of some real filet lace from the late 1800s: Now check out the collar worn by the Duke of York (the king's brother) in various scenes. On the Lace For Study site, I found no filet laces older than the 1850's, and my (admittedly limited) knowledge of filet lace is that it was common in the Rennaissance for liturgical uses, and later became a hobby for Victorian women, as tatting was. It was never the most expensive or elegant style, and wasn't considered high fashion. Would the Duke of York have worn filet lace? Never say never. Could this be intended to represent drawn-thread embroidery, instead? Also possible. Or maybe this represents a style of bobbin lace I don't know. I confess my ignorance. POINT DE FRANCE In terms of historical accuracy, Point de France is the style of lace that would have been most au courant in the 1660's. The older Italian forms (reticella and gros point) would still be deeply desired, but the newest stuff from France, produced under the aegis of Louis XIV of France, would be worn by those wealthy enough to import it. Point de France was a needlelace made with brides (bars of thread holding the motifs together), like the Italian needlelaces, but with different, more symmetrical motifs, densely clustered together. Sometimes the brides were made into a heavy honeycomb ground and covered with picots (brides picotée). Eventually, the brides were replaced with lighter mesh grounds and the motifs made smaller and more spaced out; at that point it's no longer Point de France, but Point d'Alencon or some other regional style. So, when I see symmetrically designed laces with either brides or heavy meshes with picots on them, I lean toward calling them Point de France. Here's an extant example of a bit of cravat lace from the late 1600s: All that detail, intended to be displayed in folds! Here are some cravats from the miniseries: The show also has several chemical lace collars that look much more modern in their scale and motifs, but if I have to imagine that they're historical, I'll call them Point de France, too, because they're symmetrical. It's a stretch, but I have to put them somewhere! Finally, Charles II wears a wonderful falling ruff in the scenes where he goes out into his burning city. Its scale is larger than I think quite accurate, but it's quite beautiful, and not implausible for a king who wanted to be showy. Best yet, we get some close-ups of the brides picotée, rendered in chemical lace here but easy to imagine in real needlework! Check it out! And here's the burgher he was talking to, wearing a collar I can't even dignify with a name. It might be from Target or WalMart. ;) POINT d'ALENÇON Remember when I gave an overview of the development of French needlelace? I wrote there about how, in the early days of Colbert's subsidizing of the industry, the needlelace workers imitated Italian styles of needlelace, but "about 1678 . . . the lace-workers, perhaps forgetting the traditions of the Venetian school, developed a style of their own and the work became more distinctly French, being more delicate, finer in substance, the patterns clearer and more defined" (Emily Leigh Lowes, Chats on Old Lace and Needlework). The needlelace which followed was the Alençon style, with a light mesh ground, scattered floral motifs, and raided and buttonholed cordonnet. Visit Normandy's intro to Alençon lace confirms the date of the emergence of the style, saying "until c. 1675 the new French lace strongly resembled Spanish and Venetian points and was called 'Point de France'. But around that time the lace-makers of Alençon adopted a mesh backing technique and invented a new and even more delicate stitch, a distinctive style leading to the 'Point d’Alençon' soubriquet." So, if Alençon was developing in the 1670's, it couldn't have been adorning King Charles in 1666. Nevertheless, this film does show many instances of lace which has the look of Alençon. BOBBIN LACES I am no expert in bobbin lace, so here are various styles, but I can't say much about them. SOME BLACKWORK Just for funsies... here's a blackwork shirt that seems a bit out of time. Its style is more Tudor/Elizabethan than Restoration, a hundred years out of fashion! But regardless, it's cool to see it in a movie! This scene is where the queen comes into the king's mistress' bedroom, kicks said mistress out, and gives the king a pep talk about trusting himself and ruling decisively. The king is touched (and shows it by mouth-breathing). He's wearing a velvet robe with metallic embroidery, trimmed with galloon, over a blackwork embroidered collared shirt. WORKS CITED 1666: The Great Fire of London. Documentary, written and directed by James Runcie. Presented on

YouTube. Accessed 10/23/2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycTRAJJexd4 "Alençon Lace – Frilling Stuff". Visit Normandy-Pays de la Loire. Accessed 11/19/2018: https://visitnormandy.wordpress.com/2010/11/16/alencon-lace/ Cravat end. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number: 30.135.143. Accessed 11/17/2018: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/222463 Great Fire of London: The Untold Story. Documentary. National Geographic, 2011. Accessed on YouTube, 11/13/2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBzEoyJ_5jU Lace For Study. Digital Lace Collection. Accessed 11/19/2018: http://www.laceforstudy.org.uk/ Lawless, Erin. "'The curse of the nation': Lady Castlemaine, the beautiful bitch". Blog post of 9 September 2017. Accessed 11/10/2018: https://erinlawless.wordpress.com/2013/09/09/the-curse-of-the-nation- lady-castlemaine-the-beautiful-bitch/ Lowes, Emily Leigh. Chats on Old Lace and Needlework. T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., London, 1908. Digitized by Project Gutenburg, Release Date: July 24, 2008 [eBook #26120]. Accessed 10/22/2018: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/26120/26120-h/26120-h.htm#L_V Pepys, Samuel. Diary. "Samuel Pepys Diary 1666 - Great Fire". Samuel Pepys Diary. Website. Accessed 11/17/2018: http://www.pepys.info/fire.html Robert Hubert. Wikipedia. Last edited 26 October 2018 at 6:19 UTC. Accessed 11/11/2018: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hubert Rodriguez McRobbie, Linda. "The Great Fire of London Was Blamed on Religious Terrorism: Why scores of Londoners thought the fire of 1666 was all part of a nefarious Catholic conspiracy." Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian.com. 2 September, 2016. Accessed 11/19/2018: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/great-fire-london-was-blamed-religious-terrorism- 180960332/ Unprepared: Will We Be Ready for the Megaquake in Oregon? OPB. © 2018, Oregon Public Broadcasting. Accessed 11/17/2018: https://www.opb.org/news/series/unprepared/

4 Comments

The Sister

12/11/2018 10:45:39 am

Your commentary cracks me up. Also, I want to see this mini-series! Also, if there is a huge earthquake coming to Portland, any chance of you NOT being there at the time? Just sayin'...

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Karen Roy

Quilting, dressmaking, and history plied with the needle... Sites I EnjoyThe Quilt Index Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed